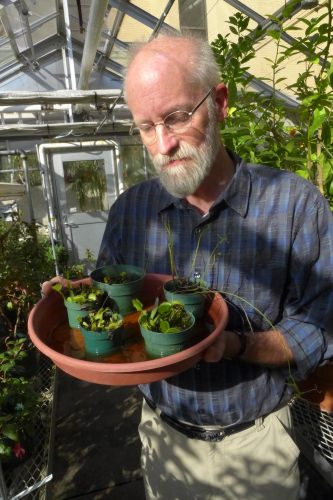

University of Wisconsin–Madison ecologists have played a key role in a petition filed with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Friday seeking emergency Endangered Species Act protection for the Venus flytrap.

The unique carnivorous plant captures flies and captivates nature lovers, but in the wild is found only in North Carolina and South Carolina.

“Kids love them, adults love them. It’s a plant that captures the imagination of everybody who sees it,” says Don Waller, a professor of botany and noted expert in conservation biology at UW–Madison. “Darwin called them a ‘most wonderful plant’ and experimented on them for several years in the greenhouse, but these plants are threatened by a combination of development, poaching and rising sea levels, and so we are asking for an expedited ‘endangered’ designation for the Venus flytrap.”

The plant’s home turf is around bogs near Wilmington, in coastal North Carolina. This is a long way from its closest relative, an aquatic plant in South Africa. The Wilmington region is growing rapidly, and the bogs are being paved and built up, Waller says.

The plant’s very popularity is another key to its undoing, he adds. “People are fascinated by a plant that can move faster than the insects it eats, but ironically one result is a market for plants stolen from the wild.”

Stolen plants are usually sold as house plants, but “many people don’t know how, or can’t be bothered, to care for them,” Waller says. “Venus flytraps are high-maintenance plants, except in their native habitat.”

The Venus flytrap uniquely evolved a “snap-trap contraption” that closes in about one-tenth of a second, enveloping its insect prey so rain does not wash the food away before the plant digests it. The flytrap has three hairs in each leaf, and a snap requires triggering more than one hair. “The insect has to hit one hair and then within a limited period hit another,” says Waller. “Only after that double signal will the leaf close. It’s a pretty clever plant.”

Neither small insects nor raindrops will trigger a snap.

As the number and size of Venus flytrap populations decline, the survivors face multiple threats: further habitat loss, diminished genetic diversity, predators and outbreaks of disease. According to the Endangered Species Act petition, a “viable population,” meaning one that is expected to survive and evolve over the long term, needs at least 1,000 plants. Only nine such populations are known.

The petition was written and signed by a national group of experts in conservation and ecology, including Waller and Tom Gibson of UW–Madison, Yari Johnson of UW-Platteville, and Robert Evans of the Virginia Natural Heritage Program.Waller has launched an online campaign in support of the petition.

[pullquote]Protection under the ESA would require the Fish and Wildlife Service to identify critical habitat for the species and takes steps to protect it, Waller says.[/pullquote]

As collectors continue to snatch plants from declining wild populations, “we have reached a situation where there are more flytraps in captivity than in the wild,” Waller says. “That might be construed as good news, if it assures they will survive in captivity, but it’s distressing for ecologists and conservation biologists. A population can only persist and evolve in its native habitat, and we’ve already seen the disappearance of 90 percent of wild plants. We have lost whole bogs, populations and individuals.”

Protection under the ESA would require the Fish and Wildlife Service to identify critical habitat for the species and takes steps to protect it, Waller says.

At stake is what Waller considers one of the most marvelous examples of evolution. “Snaptraps have only evolved once in the 3.7 billion-year history of life on Earth. This species is native to just one area of North America, and represents a unique and fascinating offshoot in the tree of life. Having plants only in greenhouses is like having tigers only in zoos. It’s not the same.”

Change is normal in biology, Waller adds. “This plant, like any species, is a process connected to an ancient past and an indefinite future. That’s what we are trying to protect. If we lose the habitat, we lose the species and its future. The world would be a poorer place without wild Venus flytraps.”