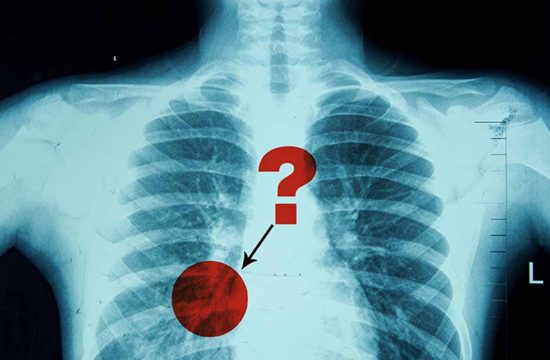

Although the reason remains unclear, a new study has found that being infected with the hepatitis B or C virus may increase a person’s risk for developing Parkinson’s disease.

Although the reason remains unclear, a new study has found that being infected with the hepatitis B or C virus may increase a person’s risk for developing Parkinson’s disease.

People can be infected with hepatitis B by coming into contact with blood or bodily fluids of an infected person. The virus affects between 850,000 and 2.2 million people in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

An estimated 2.7 million to 3.9 million people are infected with chronic hepatitis C, which can be passed through blood-to-blood contact, such as sharing razors or needles, and can be passed on at birth if the mother has the virus.

“The development of Parkinson’s disease is complex, with both genetic and environmental factors,” study author Julia Pakpoor, of the University of Oxford, said in a prepared statement. “It’s possible that the hepatitis virus itself or perhaps the treatment for the infection could play a role in triggering Parkinson’s disease, or it’s possible that people who are susceptible to hepatitis infections are also more susceptible to Parkinson’s disease. We hope that identifying this relationship may help us to better understand how Parkinson’s disease develops.”

Researchers compared hospital records from a British database, comparing people with a first case of hepatitis B or C, autoimmune hepatitis, chronic active hepatitis, and HIV, to people with more minor conditions such as knee replacement surgery, or cataract surgery. The records examined in the study were from 1999 to 2011.

The team then looked to see which participants developed Parkinson’s disease later in life.

There were records for more than 6 million people with minor conditions that were compared to nearly 20,000 people with HIV, 4,000 with chronic active hepatitis, 6,000 with autoimmune hepatitis, 48,000 with hepatitis C and nearly 22,000 with hepatitis B.

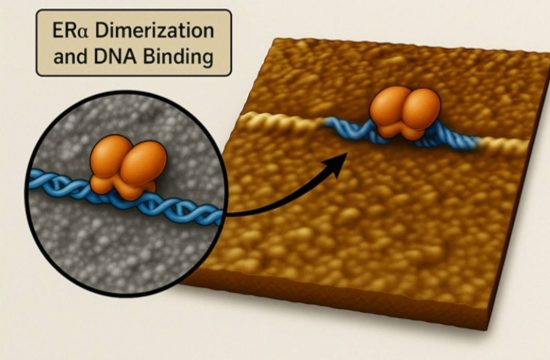

The findings, published March 29 in Neurology, showed that participants with hepatitis C were 51 percent more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease than those in the comparison group, and the increased risk rose to 76 percent for those with hepatitis B.

Specifically, there were 44 people with hepatitis B that developed Parkinson’s and 73 with hepatitis C, compared to 25 cases and 49 cases, respectively that would’ve been expected in the general population.

Interestingly, there was no increased rate of Parkinson’s disease in people with autoimmune hepatitis, chronic active hepatitis or HIV.

Some limitations of the study were that it only examined records for people evaluated at a hospital and didn’t adjust for lifestyle factors including alcohol consumption or smoking, which could affect risk, Pakpoor noted.

The development of datasets and software was funded by the British National Institute for Health Research.