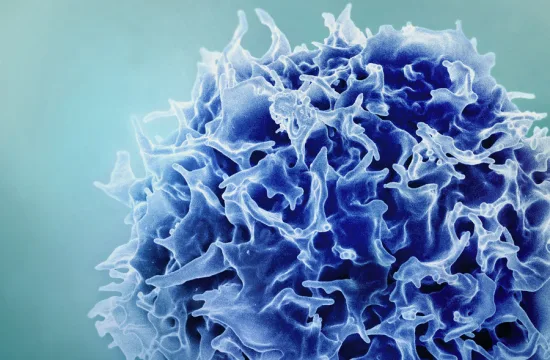

It’s well-known that physical exercise can help reduce the symptoms that people with multiple sclerosis experience, such as fatigue, muscle weakness, and walking issues.

It’s well-known that physical exercise can help reduce the symptoms that people with multiple sclerosis experience, such as fatigue, muscle weakness, and walking issues.

A new study, however, has discovered that strength training also benefits the brain—specifically by protecting the nervous system and inhibiting disease progression.

The study, published in Multiple Sclerosis Journal, was conducted by researchers at Aarhus University, University of Southern Denmark and University Medical Center Eppendorf in Hamburg. Their findings revealed a number of positive effects on the brain.

“Over the past six years, we’ve been working on an idea that targeted training affects other conditions than symptoms alone, and this study gives us the first indications that exercise protects the nervous system from the disease,” said Ulrik Dalgas, associate professor, department of public health at Aarhus University in a statement.

The randomized, controlled cross-over study enrolled 35 people with relapse-remitting multiple sclerosis. Half of the group strength trained two days a week, while the other half continued their normal life without systematic training. MRI scans were given before and after the six month trial to measure lesion load, global brain volume, percentage brain volume change and cortical thickness. Disability measures were also evaluated.

Researchers found that there was a tendency for the brain to shrink less in the patients who trained purposefully and regularly. Percentage brain volume change and higher absolute cortical thickness were observed in the exercise group.

“In sclerosis patients, the brain shrinks significantly faster than normal. Medication can reduce this change, but we found that the training further reduced shrinkage of the brain in people in medical treatment. In addition, we saw that several smaller brain areas even began to grow in response to the training, “said Dalgas.

The researchers are unsure why strength training had such positive effects, and if other patients with other types of MS would benefit. What the study does tell us is that this is an area that needs to be investigated further as a potent complementary therapy.

“Phasing out drugs in favour of training is not realistic. On the other hand, the study indicates that systematic physical training can be a far more important supplement during treatment than has so far been assumed. This aspect needs to be thoroughly explored,” said Dalgas.