Scientists have noticed first experimental evidence that cell stickiness helps them stay sorted within correct compartments during development.

But scientists have long observed that not-yet-specialized cells move in a way that ensures that cell groups destined for a specific tissue stay together.

In 1964, American biologist Malcolm Steinberg proposed that cells with similar adhesiveness move to come in contact with each other to minimize energy use, producing a thermodynamically stable structure. This is known as the differential adhesion hypothesis.

How tightly cells clump together, known as cell adhesion, appears to be enabled by a protein better known for its role in the immune system. The findings were published in the journal Nature Communications.

Kuranaga and her team conducted experiments in fruit fly pupae, finding that a gene, called Toll-1, played a major role in this adhesion process.

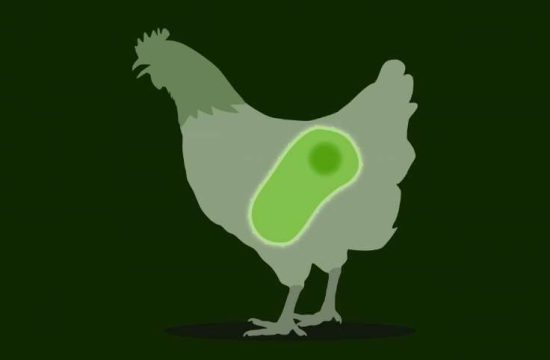

As fruit flies develop from the immature larval stage into the mature adult, epithelial tissue-forming cells, called histoblasts, cluster together into several ‘nests’ in the abdomen. Each nest contains an anterior and a posterior compartment.

Histoblasts are destined to replace larval cells to form the adult epidermis, the outermost layer that covers the flies. The cells in each compartment form discrete cell populations, so they need to stick together, with a distinct boundary forming between them.

Using fluorescent tags, Kuranaga and her team observed the Toll-1 protein is expressed mainly in the posterior compartment. Its fluorescence also showed a sharp boundary between the two compartments.

Further investigations showed Toll-1 performs the function of an adhesion molecule, encouraging similar cells to stick together. This process keeps the boundary between the two compartments straight, correcting distortions that arise as the cells divide to increase the number.

Interestingly, Toll proteins are best known for recognizing invading pathogens, and little is known about their work beyond the immune system. “Our work improves understanding of the non-immune roles of Toll proteins,” says Kuranaga. She and her team next plan to study the function of other Toll genes in fruit fly epithelial cells.