Acetylene is a gas used in many industries, including as a fuel in welding and a chemical building block for materials like plastics, paints, glass and resins. To produce acetylene, it first needs to be purified from carbon dioxide.

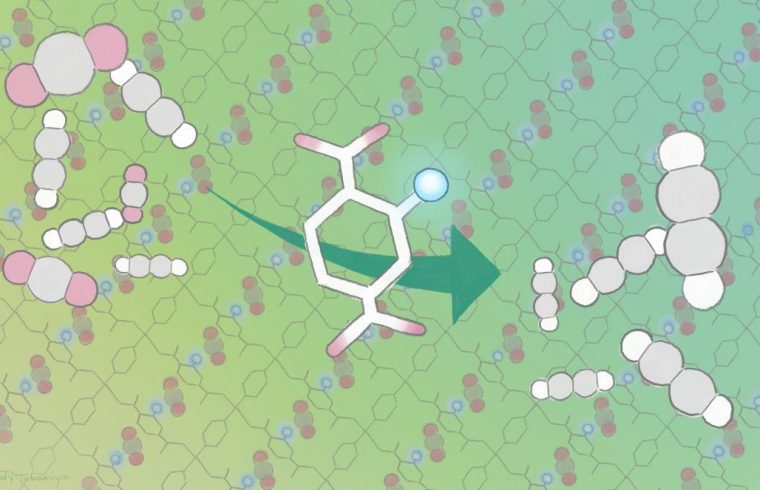

Traditionally, this is done by passing the acetylene/carbon dioxide gaseous mixture through a material. Carbon dioxide weakly interacts with the material and so passes through, while acetylene reacts strongly and becomes attached to it. The problem is that the subsequent removal of acetylene from the material takes several energy-consuming steps.

Scientists have been looking for ways to reverse this process, so that acetylene becomes the gas that passes through the material and carbon dioxide is held back. But so far, this has been very challenging.

Now, researchers have developed a more energy-efficient method that improves industrial gas purified system by reversing the traditional process. They also successfully tested and their findings were reported in the journal Angewandte Chemie International Edition.

“A problem is that both gases have similar molecular size, shape and boiling points,” explains Kyoto University’s Institute for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences (iCeMS) chemist Susumu Kitagawa, who led the study. “Adsorbents that favour carbon dioxide over acetylene do exist but are rare, especially those that work at room temperature.”

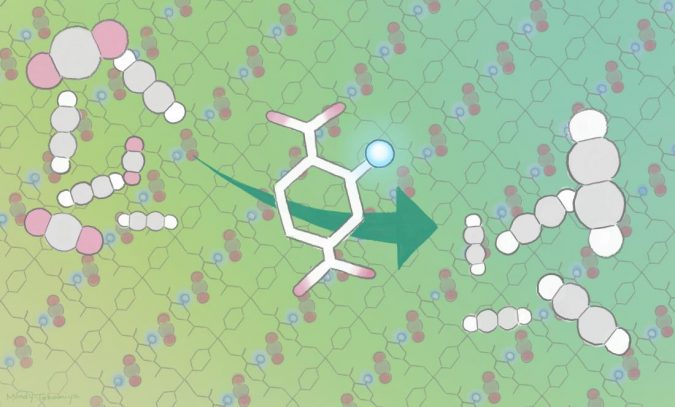

Kitagawa, iCeMS materials chemist Ken-ichi Otake and their colleagues improved carbon dioxide adsorption of a crystalline material called porous coordination polymers by modifying its pores. The team anchored amino groups into the pore channels of two porous coordination polymers.

This provided additional sites for carbon dioxide to interact with and attach to the material. The additional interaction site also changed the way acetylene bound to the material, leaving less space for acetylene molecule attachment. This meant that more carbon dioxide and less acetylene was adsorbed compared to the same material that did not have the amino group anchors.

These newly designed materials adsorbed more carbon dioxide and less acetylene compared to other currently available carbon dioxide adsorbents. They also functioned well around room temperature, and performed stably through several cycles.

“This ‘opposite action’ strategy could be applicable to other gas systems, offering a promising design principle for porous materials with high performance for challenging recognition and separation systems,” says Kitagawa.