MADISON – Over the last 50 years, income inequality between households increased significantly, but not because people changed who they marry.

According to new research led by University of Wisconsin¬–Madison professor of sociology Christine Schwartz, the tendency of people to marry those with similar jobs has not changed much. But the changing availability of spouses with particular jobs — especially a large increase in professional women — has dramatically changed common household couplings.

Because these changes in job pairings are explained by changing availability rather than new preferences, marriage choices based on jobs have contributed little to income inequality. In fact, if matching based on occupation were completely random, the increase in inequality between households since 1970 would be just 5% lower than it is today.

Instead, the income gaps between people in similar jobs and between different kinds of jobs explain the vast majority of the rise in household income inequality, which has increased by 49% since 1970.

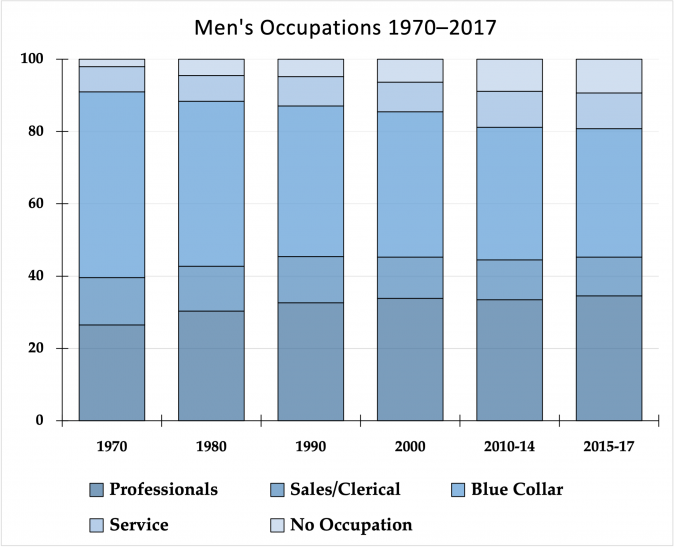

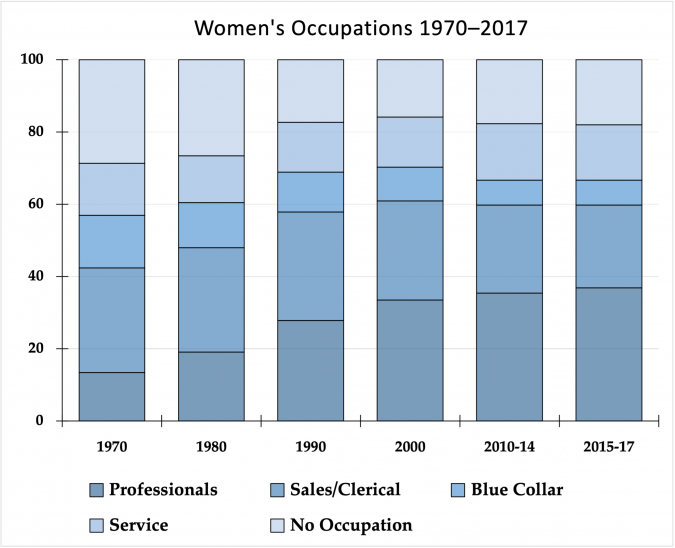

Seismic shifts in the economy have led to large differences in the jobs men and women hold over the last half century. In particular, the share of professional women almost tripled to roughly 35%, and more women entered the labor force. Over the same period, men became less likely to work in blue-collar jobs, and somewhat fewer men worked.

These trends have affected marriage patterns and led to a pronounced increase in the number of dual-professional households.

“There have been giant changes in who people are married to, but those seem to be mostly the result of broad economic changes. Because we found all of these changes were really about the availability of potential partners in different jobs, the actual changes in matching beyond that were basically nonexistent,” says Schwartz.

The researchers also found that married men, but not married women, have seen a decline in income due to a combination of stagnant wages, a modest decrease in the percentage of men working, and a drop in relatively well-paying blue-collar jobs. In many sectors, wives have offset flat wages among husbands and low wage growth within occupations by increasing their share in the labor force and by occupying better-paying professional jobs at greater rates.

“For men, the changes in women’s occupational structures mean their wives have higher occupational earnings today,” says Schwartz. “But for women that’s not true. The average occupational earnings for the husbands of these women have declined.”

These findings, which Schwartz published Aug. 8 in the journal Social Science Research with collaborators at Duke Kunshan University and the University of California, Los Angeles, emerged from studies of marriage habits — called assortative mating — and income inequality.

The team analyzed the trends over the last half century in occupational assortative mating, or the tendency of people to marry those with similar jobs. Using census data, Schwartz and her colleagues studied more than four million married opposite-sex couples and their jobs from 1970 to 2017.

Due especially to the increased representation of women in professional jobs, dual-professional marriages became by far the most common coupling among 25 possible pairings of job categories. By 2017, nearly a quarter of all married couples were made up of two professionals, compared to just 7% in 1970. Men in all jobs have become far more likely to be married to professional women.

At the same time, once-common pairings have become rarer. Fifty years ago, more than 1 in 10 marriages were between two blue-collar workers. Today, it’s just 3.5%. Fifteen percent of marriages were between blue-collar husbands and wives who didn’t work in 1970, and that has now shrunk to 6.5% of marriages. Due to the drop in men working blue-collar jobs, most pairings with blue-collar men have declined.

When Schwartz’s team controlled for the availability of spouses in different professions, they discovered that nearly all of the changes in household couplings are due to the differences in jobs individuals have, rather than new patterns in marriages.

For instance, male doctors 50 years ago had a similar tendency to marry female doctors as they do now. There are just many more female doctors today, which allows more two-doctor households to exist.

The occupational trends challenge our assumptions, says Schwartz: “There’s this idea that assortative mating should increase inequality across households if, say, doctors marry other doctors when they once may have married nurses. That has seemed really intuitive to people. But the research hasn’t borne that out.”