The first lunar samples to arrive on Earth in nearly 45 years are revealing unexpected insights into the thermal and chemical evolution of the moon.

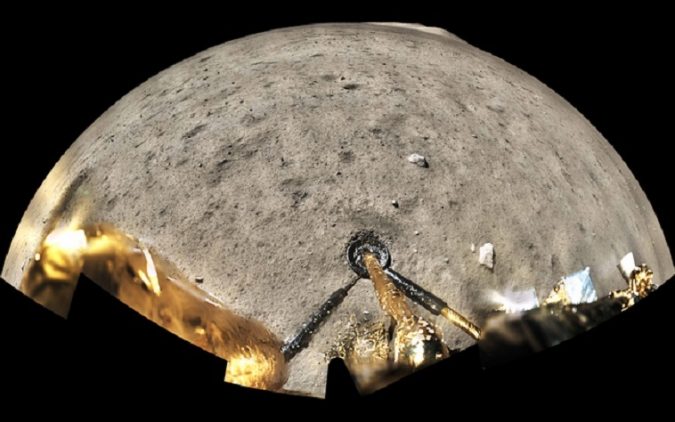

On Dec. 17, 2020, China’s Chang’E-5 mission returned roughly 3.8 pounds of lunar material to Earth for analysis—the first sample retrieved from the moon since the Soviet Union’s last Luna mission in 1976. A new analysis of the samples has scientists reevaluating what we thought we knew about the moon, including the last known data of volcanic activity, water distribution, and the composition of the rocks that litter the surface. Chinese scientists published their findings in three separate Nature papers this week.

The landing site of the Chang’E-mission, known as the Ocean of Storms, was selected for being one of the youngest mare basalt units, formed by volcanic eruptions. Additionally, the region covers more than 10% of the lunar surface.

“Returned lunar samples from six Apollo and three Luna missions in the last century have significantly enhanced our understanding of the Moon’s history and evolution,” said project leader LI Xianhua, of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. “However, that sampling focused on areas that do not represent the most widespread lunar surface features. These limited sampling sites have restricted new understandings of the moon.”

Previous radioisotope dating of lunar samples suggested that most lunar volcanic activity ceased around 2.9-2.8 billion years ago. But according to Xianhua and colleagues, the new samples are 2.03 billion years old—extending the reported duration of lunar volcanic activity by 800 to 900 million years. The study authors say this younger aging also demonstrates that the moon’s interior was still evolving 2 billion years ago.

The composition of the basalts was examined in multiple studies. In one such example, researcher Hu Sen and team found that the magma of the 2-billion-year-old basalts contained less water than samples from regions with basalts that are dated at 4 to 2.8 billion years old.

“This suggests the source of the younger basalts became dehydrated during prolonged volcanic activity, consistent with the notion that volcanic activity continued until at least 2 billion years ago,” explains the study authors.

In another study, Yang Wei and his team discovered that the younger basalts contained lower levels of heat-producing elements than expected, indicating that the moon may have cooled off more slowly than previously thought, which would affect mantle dynamics. These results from Wei and colleagues may provide a basis for exploring new models for the thermal evolution of the moon.

Finally, work by Li Chunlai, a researcher at the National Astronomical Observatories of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, questions previous studies that have indicated craters on the moon were produced by impacts.

Chunlai and his team took 316,800 images of the new lunar samples, revealing that, chemically, they are free of evidence of impact debris and seem to be of lunar origin. The scientists said the samples have most of the characteristics of basalt but are lower in magnesium and higher in iron than the basalt typically found on Earth.

“This could represent a new class of basalt,” said Chunlai. “This compositional information suggests that CE-5’s samples might represent a new lunar basalt different from previous Apollo and Luna missions.”

Chunlai stressed that these studies represent only the preliminary examination of the first lunar samples brought back to Earth in 45 years.

“These samples will open an epoch-making window for studying lunar science. We’ve already found that the moon is so vast and more heterogenous than we thought, so more missions to collect samples should be scheduled,” he concluded.

—LE