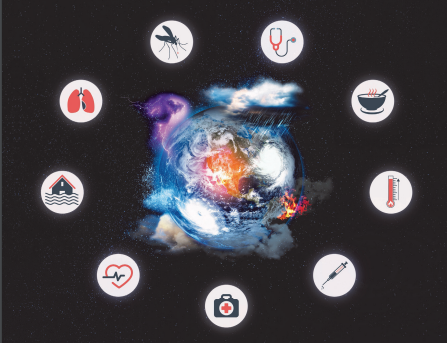

Climate change threatens the health of billions of people, especially those who contribute least to climate change, but many strategies to cut greenhouse gas emissions can improve health in the near term.

The new report ‘Health in the climate emergency – a global perspective‘, launched today by the InterAcademy Partnership (IAP), examines how the climate crisis is affecting health worldwide and calls for urgent action: “Billions of people are at risk, therefore we call for action against climate change to benefit health and also advance health equity”, says Robin Fears, IAP project coordinator and co-author of the IAP report.

According to IAP, in a three-year global project, IAP has worked together with its regional networks in Africa (NASAC), Asia (AASSA), the Americas (IANAS), and Europe (EASAC) to capture diversity in evaluating evidence from their own regions to inform policy for collective and customized action at national, regional and global levels. A team of more than 80 scientists from all regions of the world has contributed to the project.

Analyzing extensive scientific evidence, the recent report offers a global review of the current knowledge and examines how climate change and its drivers are acting through a range of direct and indirect pathways to impact, for example: heat-related mortality and morbidity, extreme events such as floods and droughts, decreases in crop yield in some regions, changes in the distribution of vector-borne diseases and wildfires causing widespread exposure to air pollution.

Generally, a wide range of health outcomes is affected including cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, water and food-borne diseases, undernutrition, and mental health. There is also a growing risk of forced migration with its attendant adverse health consequences.

An article published in Nature Climate Change, summarised in the IAP report, shows for example that one-third of heat-related deaths over recent decades can be attributed to climate change according to analysis of data from over 700 sites in 43 countries (Vicedo-Cabrera et al, 2021).

Moreover, other studies have found that extreme heat exposure reduces the ability to undertake physical labour, with a Lancet Planetary Health paper stating that approximately one billion people globally are projected to be unable to work safely for part of the year (even in the shade) after an increase in the global temperature of about 2.5o C above pre-industrial (Andrews et al, 2018).

“Many policies and actions that reduce greenhouse gas emissions also benefit health in the near term as well as reducing the risks of dangerous climate change”, says Andrew Haines, Professor of Environmental Change and Public Health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) and co-chair of the IAP project. Haines is the winner of the 2022 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement – often regarded as the ‘Nobel Prize for the Environment.

For instance, fine particulate air pollution arises from many of the same sources as emissions of greenhouse gases. Fossil fuel- and biomass-related emissions account for a substantial proportion of the total health burden from ambient pollution. According to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), phasing out these anthropogenic sources of air pollution is projected to avert millions of premature deaths worldwide each year (Lelieveld et al, 2019).

Climate change is already reducing food and nutrition security and, unless tackled, will have ever greater impacts on undernutrition and deaths. IAP underlines that promoting dietary change – increasing consumption of fruit, vegetables, and legumes and reducing red meat intake, where that is excessive – could have major health and environmental benefits. Such diets would enable significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions from food systems as well as reducing water and land use demands. Furthermore, through the reduced risk of heart disease, stroke, and other conditions, there would be major reductions in non-communicable disease burden.

Climate action could also avert a significant increase in the spread of infectious diseases. For example, a study published in the Lancet Planetary Health estimates that the population at risk of both dengue and malaria might increase by up to 4.7 billion additional people by 2070 relative to 1970-99, particularly in lowlands and urban areas (Colon-Gonzalez et al, 2021). Thus IAP calls for strengthening communicable disease surveillance and response systems that should be a priority for improving adaptation to climate change worldwide.

The IAP report stresses that climate change affects the health of all people, but the burden is not distributed evenly or fairly.

“Instead, it falls most heavily on those in low socio-economic conditions and marginalized people, and is influenced by intersecting factors such as health status, social, economic, and environmental conditions, and governance structures. Climate change impacts exacerbate inequities and injustices already experienced by vulnerable populations, many of which are founded in colonialism, racism, discrimination, oppression, and development challenges”, says Sherilee Harper, Associate Professor at the University of Alberta, Canada and Co-author of the report.

“We emphasize that health-related adaptation efforts must prioritize Indigenous Peoples, aging populations, children, women and girls, those living in challenging socio-economic settings, and geographically vulnerable populations.”

Globally, groups that are socially, politically, and geographically excluded are at the highest risk of health impacts from climate change, yet they are not adequately represented in the evidence base.

“Therefore, equity at the local, regional and international scale must be at the forefront of research and policy responses”, says Volker ter Meulen co-chair of the IAP project. “Equity is at the core of effective responses.”

IAP calls all stakeholders to take action in building climate–health resilience that will limit future risks. The very wide geographical coverage of IAP is invaluable in helping to communicate the voices of those – from low- and middle-income countries and vulnerable populations – who are not always heard during the processes whereby evidence informs international policy.

“Investing in climate-resilient infrastructure, healthcare systems, and policies will support adaptation and decrease future health risks from climate change”, adds ter Meulen. “A ‘health in all policies’ response will support climate change adaptation and mitigation actions to help meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, will have co-benefits for health, and will support the achievement of key international initiatives such as the Sustainable Development Goals.