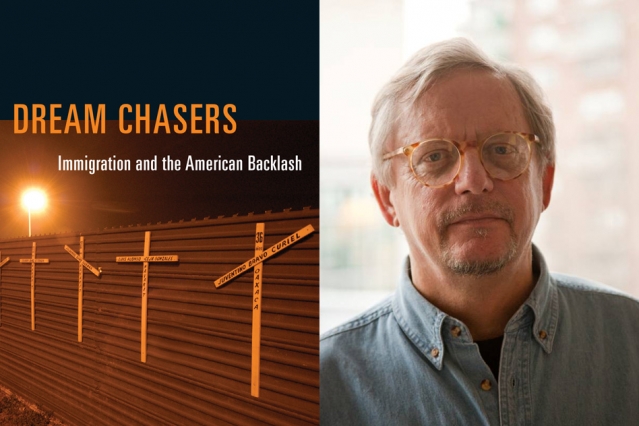

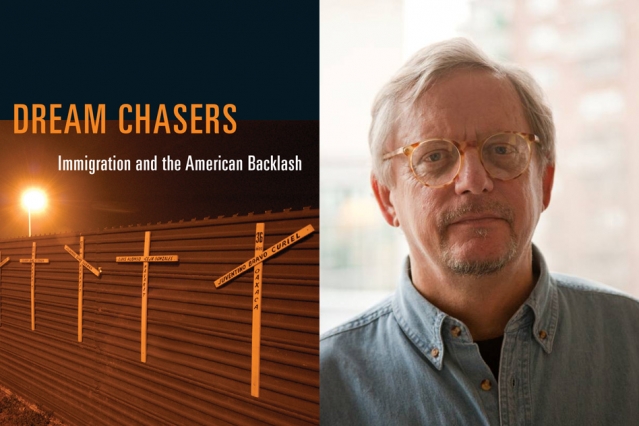

MIT scholar’s new book explores fierce debates over immigration.

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Immigration policy has been among the most rancorous of U.S. political issues in recent years. What has been fueling America’s contentious debates over the topic?

Security, according to many people: In the time since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, keeping borders secure has been a main justification for tightly controlled immigration. But underneath those concerns lies a simmering cultural clash, according to one MIT scholar who has been studying the topic in depth recently.

“It’s about some larger loss of U.S. identity,” says John Tirman, executive director of MIT’s Center for International Studies. Opponents of immigration, he adds, “say they’re not concerned about culture, use of language, and changing norms, but I think it really does come down to those kinds of issues.”

And in the last two decades, Tirman thinks, that has specifically meant a fight about the relationship between U.S. identity and Latin American culture, in light of the large numbers of Latino immigrants who have come to the country. Disputes about language use, school curricula, and other cultural issues have made this evident, Tirman says.

“The way the reaction to illegal immigration has manifested indicates most clearly that the resistance is mainly one of cultural difference and exclusion … rather than economics or politics,” writes Tirman in his new book on the subject, “Dream Chasers,” just published by the MIT Press.

Class conflict

While Tirman says there are many places to find these cultural clashes over immigration, his book focuses on a few case studies, such as an educational dispute that spilled into the state legislature in Arizona. In Tucson, some schools adopted a Mexican-American Studies (MAS) program teaching the region’s history from an alternate point of view, with a much greater emphasis on the historic presence of Mexicans in the area, and a more critical interpretation of U.S. actions.

The MAS program seemed to have a beneficial effect on Latino students, keeping them engaged and helping their academic standing. But by 2010, the state’s superintendent of schools and legislators effectively shot down the program, introducing new policies eliminating the curriculum from schools, despite its apparent success.

The Tucson schools controversy had nothing to do with security matters, Tirman observes. Instead it showed, he writes in the book, “the fissures in Arizona’s political culture when it came to the sensitive issues immigration brought to the fore — race and ethnicity, language, jobs, education, and, at root, what it means to be an American.”

It also indicates that a greater immigrant presence is accompanied by a greater backlash against those new residents; Arizona is now 30 percent Latino, but, as Tirman notes, has become “the leading anti-immigration-reform state,” as well.

To be sure, Tirman allows, clashes over “culture” are often heightened by difficult economic circumstances; as middle-class wages have stagnated in recent decades, immigration has become more of a hot-button issue. In all, 45 states have passed immigration restrictions (on top of federal law) in the last two decades.

“I think there’s no question that the resistance to immigration grows more voluble during times of economic stress,” says Tirman, while noting that the current debate is “more contentious” than it was in the more rosy economic circumstances of the 1990s. More recently, he notes, “George W. Bush’s reform package of 2006-2007 was shot down at a time when the economy was beginning to weaken. And the economy has been rocky ever since, so it’s no surprise there’s been opposition to the more recent reform efforts.”

The long march

Tirman, for his part, believes the future holds both wider tolerance of immigrants from Latin America among most U.S. citizens, but a continued resistance to loosening immigration law on the policy level.

Polling, he notes, shows that a majority of Americans seem amenable to reforms such as the ones both Bush and President Barack Obama have proposed, even as Congress prefers not to take action on the matter.

“The public has moved a long way in the last 20 or 30 years toward acceptance, and I think that’s based on a kind of recognition that we’ve had all these people here, 11 million [undocumented immigrants], not really doing much harm,” says Tirman, who himself favors a more open set of immigration laws.

At the same time, he notes, the generally sluggish global economy, particularly in Mexico and some part of Latin America, may only provide more impetus for people to migrate to the U.S. without documented status. And that heightened presence could also fortify resistance to immigration among the Americans already set against it.

“We are going to be having these issues for a long, long time,” Tirman says, “so we had better understand their origins.”