Two weeks ago, in a precursor event to COP21, over 2,000 top-of-their-field scientists gathered in Paris to present their ideas and solutions on how best to protect our world. This article is the first in a series based on the findings presented.

- By Aya Lowe, ResearchSea

Last week, over 2,000 top-of-their-field scientists gathered in Paris to present their ideas and solutions on how best to protect our world, which has for a long time been on a dangerous path to self destruction through climate change.

This event, called “Our Common Future under Climate Change”, was the precursor to the Conference of Parties 21 (COP21) on climate change scheduled for this December in Paris. It comes at a very exciting/scary time depending on how you look at it.

It’s exciting because over the past year, the number of countries signaling their support for a long-term vision on climate change has risen dramatically. This has led to more R&D investment, more research and more strides towards policy actions that aim to create a carbon neutral world. Some nations such as China have set long-term targets ranging from 100 per cent renewable energy by 2050 to absolute emission reductions – in China’s case of 65 per cent. With these pledges come a slew of new technologies and innovations aimed at achieving the ambitious targets.

It’s scary because while a dramatic reduction in carbon emissions and boosting of energy efficiency are possible, it’s going to be a long hard road to achieve these targets and even longer before we will feel the effects of these new technologies.

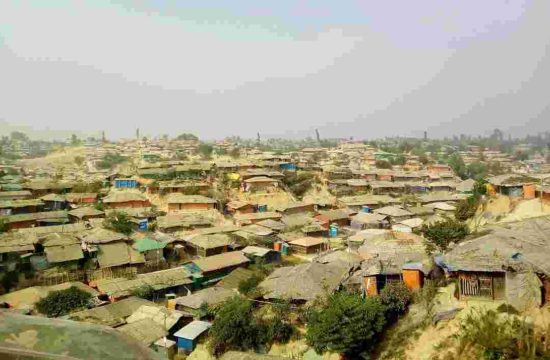

One target of COP21 is to keep the global temperature rise to under 2 degrees Celsius this century, which is no easy feat. Warming to 2°C or less will require a carbon budget that limits future carbon dioxide emissions to about 900 billion tonnes, roughly 20 times the world’s combined annual emissions in 2014. Even if governments achieve their goals for curbing global warming, sea levels are predicted rise by at least six metres in the long term, swamping low-lying coastal areas such as Bangladesh.

In order to achieve this, renewable and clean energy sources will have to become a vital part of the energy mix.

According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance US$2.5 trillion will be spent on renewable technologies in Asia Pacific by 2030.

China which is the region’s energy giant, accounting for almost half of global coal use, has been making big stride in reducing its carbon emission by installing solar, wind and other renewable technologies. According to Xin Li, a fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, China’s wind turbines alone are expected to produce nearly two and a half times the entire power generating capacity of Britain by 2020.

However while China can act as a role model for other Asian countries, the reality is that to support their economic growth, they will still need the cheapest large-scale source of energy available regardless of the impacts on climate. Unfortunately, this is usually coal.

According to Joyashree Roy, a professor of economics at Jadaypur University the government of India has started talking about carbon price and tax and building up a national clean energy fund, which is not going to be an easy feat. Coal provides the overwhelming majority of India’s energy. “We need to leave three quarters of the coal reserves in the ground which is not going to be easy because there’s so much capital embedded in it,” she said.

Outside of China, India, Japan and South Korea, renewable power capacity in Asia is expanding about 5 percent a year. But because it starts from such a low base, clean sources will provide only about 3 percent of the region’s electricity by 2040.

At the CFCC, there were some who were of the belief that it might be too late to just rely on clean energy.

“We should have done this 20 to 30 years ago. This means we will probably overshoot the target of 2 degrees and will have to resort to advance technologies such as taking carbon out of the atmosphere biomass and carbon capture storage,” said Nebojsa Nakicenovic, Professor Emeritus of Energy Economics, TU Wien, Austria.

Discussions at the Paris event dissected these various energy innovations, looking at their benefits and hindrances. In her keynote speech, Dr. Sally Benson, professor of energy resources enginering at Stanford University and directors of the Global Climate and Energy Project (GCEP) outlined the direction of future innovations and technology.

“First we need to decrease reliance on depletable energy resources, second we need to increase utilisation of local resources improving energy security, and we [also] need to radically reduce energy intensity and radically reduce carbon necessity. In order to do this, we need new technologies that can be deployed at a large scale and low cost. These are technologies that can shift the paradigm from the current situation today to a much broader portfolio of energy solutions to low carbon intensity,” she explained.

Dr Benson outlined some key technology game changers now being used as wind, photovoltaics and natural gas. For the near future, she listed information technology, energy technology, electric cars and grid-scale energy storage as the game changers in a period where customers will not only consume but also participate in energy systems. And looking further ahead, she listed carbon capture and storage, abiotic renewable fuels (effectively renewable fossil fuels) and passive radiative cooling (cooling that doesn’t require electricity) as the future game changers.

While these new technologies offer a vision of a carbon neutral future, technologies such as Carbon Capture Storage is still in its development stage so is very expensive and out of reach for many countries within South East Asia.

“Given CCS is still in the development phase, we have to pay to advance research, and public money is not going to be enough,” said Corinne Le Quere, director of the Tyndall Centre, a climate research centre at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom.

While energy technology innovation will be essential, on its own it is unlikely to deliver on our climate targets and should therefore be combined with non technology innovations such as social or business model innovation. For example, Frank Geels, a professor of system innovation and sustainability at the University of Manchester emphasizes the importance of a bottoms up approach where citizen themselves should take the issue of climate change into their own hands and do actions such as buy electric cars rather than rely too much on the rules of new policy or market tools like carbon pricing which is what is being done in Singapore. The government has been encouraging their citizens to educate themselves about the issue and as consumers make climate conscious decisions.

“We are encouraging through ownership, through social media outlets as well as through events and programmes and partnering with corporates, to do more outreach whether it is in the school segment or the community. That goes for energy audits and consumer understanding of green products,” said Isabella Loh, chairman of the Singapore Environment Council.

Scientists at the CFCC conference have recognised the need to bring together various disciplines on a common issue such slowing down the effects of climate change to find solutions that integrate technology, socio-economic aspects and risk assessments.

“This conference is really about bringing different countries, cultures and scientific perspectives to take stock and get a more comprehensive understanding of climate change and the possible solutions. It is a chance to take a closer look at research that is likely to shed light for negotiators on what solutions are currently implementable and available,” said Herve Le Treut, Chair of the Organising Committee for the Our Common Future Under Climate Change conference.

While technology development and mitigation efforts will play a big part in reducing the effects of climate change, the ongoing effects are unavoidable and so, as many scientists pointed out in their presentation, we will have to rely on adaptation in the short term. But there are limits to adaptation.