|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

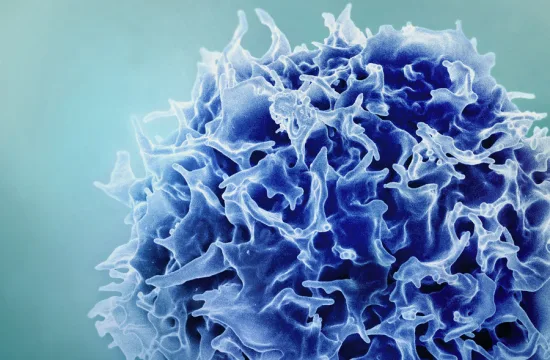

MADISON – About 44 percent of working people diagnosed with metastatic cancer continue to work after their diagnoses, according to a new study by a UW Carbone Cancer Center oncologist.

MADISON – About 44 percent of working people diagnosed with metastatic cancer continue to work after their diagnoses, according to a new study by a UW Carbone Cancer Center oncologist.

The study, led by Dr. Amye Tevaarwerk, a breast cancer oncologist who is a specialist in cancer survivorship, found that symptoms related to the cancer often determined whether people were able to remain at work after their diagnoses and showed the need for better symptom management so that patients can maintain their employment.

The study was published online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

Tevaarwerk and colleagues analyzed data from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group’s “Symptom Outcomes and Practice Patterns (SOAPP)” to investigate which factors are associated with employment changes among patients with metastatic cancer.

[pullquote]Tevaarwerk says that better control of symptoms could help more patients continue to achieve their goal of remaining employed.[/pullquote]

Among the 668 patients in the analysis, 236 (35 percent) worked full- or part-time while 302 (45 percent) stopped working due to illness. The percentage of patients working despite metastatic cancer was 44 percent, discounting those who were not working at the time of metastatic diagnosis. Overall, 58 percent reported some change in employment due to illness.

“For patients with metastatic cancer, a great deal of attention is focused on the events surrounding initial diagnosis of disease and the issues surrounding the end-of-life,” Dr. Tevaarwerk notes. “However, between cancer recurrence and the end-of-life, these patients are living their lives day-to-day and there are a number of unique survivorship issues during this time that have been overlooked by researchers.”

After comparing patients who were stably working with those who were no longer working, Tevaarwerk and colleagues found that one of the most significant factors associated with no longer working was a high burden of symptoms. Surprisingly, the type of cancer treatment, type of cancer, and time since diagnosis did not seem to affect employment.

Tevaarwerk says that better control of symptoms could help more patients continue to achieve their goal of remaining employed.

“These results show why it is important that we explore with our patients what is important to them and what they are hope for,” says Tevaarwerk. “Based on our data, we expect roughly one-third patients will either want to work or need to work for financial reasons. This is actually close to what I have seen in clinical practice, and the issue of how long to work, or the need to work comes up frequently. Efforts to control symptoms may enable more of our patients to achieve this particular goal.”

Metastatic cancer means the cancer has spread from its original cells to other areas of the body. Improved treatments have helped to prolong the lives of patients with metastatic cancer. Because people diagnosed with metastatic cancer may wish to continue to work, Tevaarwerk says understanding how their illness affects their employment may help patients make adjustments.