Material could harvest sunlight by day, release heat on demand hours or days later.

CAMBRIDGE, Mass.–Imagine if your clothing could, on demand, release just enough heat to keep you warm and cozy, allowing you to dial back on your thermostat settings and stay comfortable in a cooler room. Or, picture a car windshield that stores the sun’s energy and then releases it as a burst of heat to melt away a layer of ice.

According to a team of researchers at MIT, both scenarios may be possible before long, thanks to a new material that can store solar energy during the day and release it later as heat, whenever it’s needed. This transparent polymer film could be applied to many different surfaces, such as window glass or clothing.

Although the sun is a virtually inexhaustible source of energy, it’s only available about half the time we need it — during daylight. For the sun to become a major power provider for human needs, there has to be an efficient way to save it up for use during nighttime and stormy days. Most such efforts have focused on storing and recovering solar energy in the form of electricity, but the new finding could provide a highly efficient method for storing the sun’s energy through a chemical reaction and releasing it later as heat.

[pullquote]For the sun to become a major power provider for human needs, there has to be an efficient way to save it up for use during nighttime and stormy days.[/pullquote]

The finding, by MIT professor Jeffrey Grossman, postdoc David Zhitomirsky, and graduate student Eugene Cho, is described in a paper in the journal Advanced Energy Materials. The key to enabling long-term, stable storage of solar heat, the team says, is to store it in the form of a chemical change rather than storing the heat itself. Whereas heat inevitably dissipates over time no matter how good the insulation around it, a chemical storage system can retain the energy indefinitely in a stable molecular configuration, until its release is triggered by a small jolt of heat (or light or electricity).

Molecules with two configurations

The key is a molecule that can remain stable in either of two different configurations. When exposed to sunlight, the energy of the light kicks the molecules into their “charged” configuration, and they can stay that way for long periods. Then, when triggered by a very specific temperature or other stimulus, the molecules snap back to their original shape, giving off a burst of heat in the process.

Such chemically-based storage materials, known as solar thermal fuels (STF), have been developed before, including in previous work by Grossman and his team. But those earlier efforts “had limited utility in solid-state applications” because they were designed to be used in liquid solutions and not capable of making durable solid-state films, Zhitomirsky says. The new approach is the first based on a solid-state material, in this case a polymer, and the first based on inexpensive materials and widespread manufacturing technology.

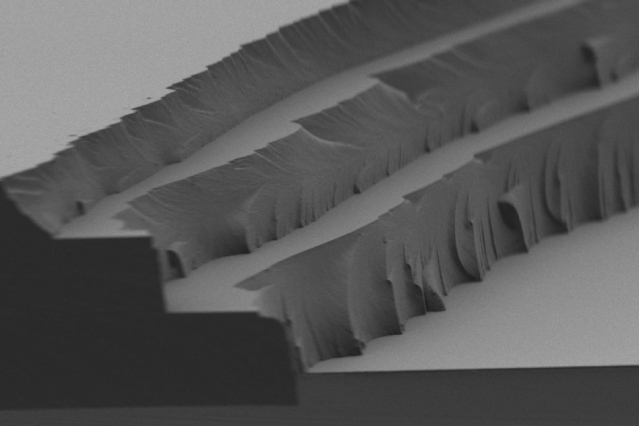

Manufacturing the new material requires just a two-step process that is “very simple and very scalable,” says Cho. The system is based on previous work that was aimed at developing a solar cooker that could store solar heat for cooking after sundown, but “there were challenges with that,” he says. The team realized that if the heat-storing material could be made in the form of a thin film, then it could be “incorporated into many different materials,” he says, including glass or even fabric.

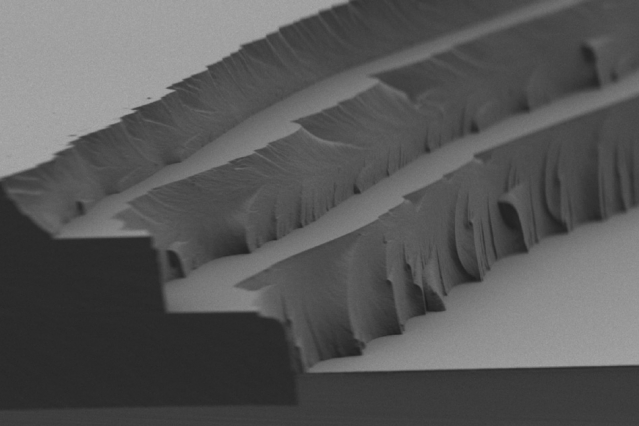

To make the film capable of storing a useful amount of heat, and to ensure that it could be manufactured easily and reliably, the team started with materials called azobenzenes that change their molecular configuration in response to light. The azobenzenes can then can be stimulated by a tiny pulse of heat, to revert to their original configuration and release much more heat in the process. The researchers modified the material’s chemistry to improve its energy density — the amount of energy that can be stored for a given weight — its ability to form smooth, uniform layers, and its responsiveness to the activating heat pulse.

Shedding the ice

The material they ended up with is highly transparent, which could make it useful for de-icing car windshields, says Grossman, the Morton and Claire Goulder and Family Professor in Environmental Systems and a professor of materials science and engineering. While many cars already have fine heating wires embedded in rear windows for that purpose, anything that blocks the view through the front window is forbidden by law, even thin wires. But a transparent film made of the new material, sandwiched between two layers of glass — as is currently done with bonding polymers to prevent pieces of broken glass from flying around in an accident — could provide the same de-icing effect without any blockage. German auto company BMW, a sponsor of this research, is interested in that potential application, he says.

With such a window, energy would be stored in the polymer every time the car sits out in the sunlight. Then, “when you trigger it,” using just a small amount of heat that could be provided by a heating wire or puff of heated air, “you get this blast of heat,” Grossman says. “We did tests to show you could get enough heat to drop ice off a windshield.” Accomplishing that, he explains, doesn’t require that all the ice actually be melted, just that the ice closest to the glass melts enough to provide a layer of water that releases the rest of the ice to slide off by gravity or be pushed aside by the windshield wipers.

The team is continuing to work on improving the film’s properties, Grossman says. The material currently has a slight yellowish tinge, so the researchers are working on improving its transparency. And it can release a burst of about 10 degrees Celsius above the surrounding temperature — sufficient for the ice-melting application — but they are trying to boost that to 20 degrees.

Already, the system as it exists now might be a significant boon for electric cars, which devote so much energy to heating and de-icing that their driving ranges can drop by 30 percent in cold conditions. The new polymer could significantly reduce that drain, Grossman says.

The work was supported by a NSERC Canada Banting Fellowship and by BMW.