CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Want to encourage innovation? A new study co-authored by an MIT professor finds that little-known state laws called “constituency statutes” have significant effects on the quantity and quality of innovative business actions.

The statutes, which allow companies to prioritize the interests of “stakeholders” — often employees — rather than just shareholders, tend to allow businesses more time to bring innovations to market, rather than forcing those companies to prioritize quarterly financial results at the exclusion of new products and new activities.

“Constituency statues are pretty important,” says Aleksandra Kacperczyk an associate professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management and an author of a new paper detailing the study.

[pullquote]The statutes appear to have helped firms especially in the areas of clean energy and consumer goods.[/pullquote]

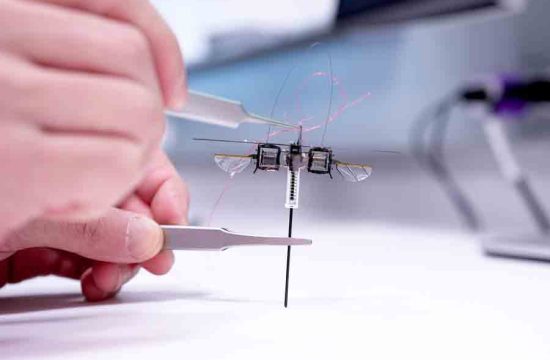

Overall, constituency states, which exist in 34 U.S. states and were largely introduced in the 1980s, raise the rate of patenting among firms by at least 6.4 percent, according to the study.

“When the company is more stakeholder-focused, one very concrete consequence is that workers are being more protected,” explains Kacperczyk, who is the Fred Kayne (1960) Career Development Professor of Entrepreneurship. “And we know from some other [research] that when that happens, then people are more willing to engage in risk-taking, which is very conducive to innovation. … Breakthrough ideas take time and [can] put your career at stake.”

Moreover, the number of citations per patent filed in states with constituency statutes rises by at least 6.3 percent, the study shows.

“There were not only more patents, but they were more original and influential, “ Kacperczyk adds.

The study is published online in the journal Management Science. Along with Kacperczyk, the other author is Caroline Flammer, an assistant professor at the University of Western Ontario.

A trade-off to obtain innovation

To conduct the study, the researchers used the so-called “differences in differences” methodology to analyze the changing rates of patent activity in the 34 states with constituency statutes, versus activity rates in the 16 states lacking them.

The statutes appear to have helped firms especially in the areas of clean energy and consumer goods.

“Increasingly, companies are engaging consumers in innovation,” Kacperczyk notes.

Ohio was the first state to adopt a constituency statute, in 1984, and Texas is the most recent to have done so, in 2006. The study looked at roughly 160,000 examples of firm performance in the U.S., using data from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Patent Data Project, as well as Standard & Poor’s Compustat database of financial information for companies.

The key mechanism at work, Kacperczyk emphasizes, is the “trade-off that you face between short-term profits and the long-term view, in that innovation takes longer to develop. … There has been consistent evidence that the market in the short term doesn’t recognize [this] value.”

Rather than feeling pressure to, say, cut a research and development group to boost the short-term bottom line, the laws enable company management to keep betting on innovation investment even when it does not maximize shareholder value at every given moment.

Warding off takeovers

In the study, the researchers do address potentially complicating factors that might seem to make the connection between constituency statutes and innovation merely coincidental. For instance: Could it be the case that innovative firms successfully lobbied to have constituency statutes enacted, and that the increase in patenting would have happened anyway?

Actually, no: Constituency statutes were often implemented to ward off potential hostile takeovers of in-state companies, in which certain investors attempt to seize control of firms to maximize short-term shareholder value.

“Hostile takeovers can be detrimental to workers and communities, so they really needed this,” Kacperczyk says. “This is precisely when the interests of shareholders are being pitted against the interests of stakeholders. You need the stakeholder supremacy model to protect the interests of stakeholders.”

Indeed, Kacperczyk concludes, constituency statutes do help a firm’s financials, but over a lengthier period of time than takeover specialists sometimes want.

“It’s better for the bottom line,” Kapcerczyk says. “To the extent that shareholders care about profits, then in the long run it aligns with shareholder interests. It’s a way of thinking about how to create value for both stakeholders and shareholders.”