Scientists graphene coat cells to keep them alive and wet even in vacuum, significantly advancing the field of bioimaging

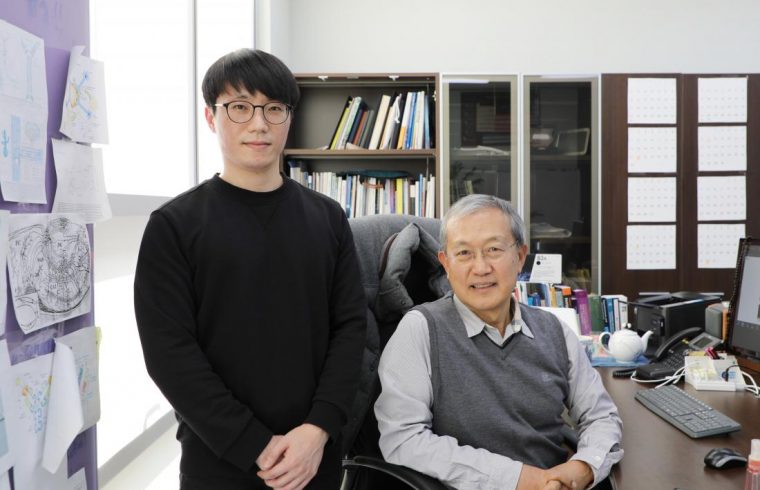

Researchers from Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Technology (DGIST), Korea have now found a way to keep living, wet cells viable in an ultra-high-vacuum environment, using graphene, allowing—like never before—accurate high-resolution visualization of the undistorted molecular structure and distribution of lipids in cell membranes.

This could enhance our bioimaging abilities considerably, improving our understanding of mechanisms underlying complex diseases such as cancers and Alzheimer’s.

With every passing day, human technology becomes more refined and we become slightly better equipped to look deeper into biological processes and molecular and cellular structures, thereby gaining greater understanding of mechanisms underlying diseases such as cancer, Alzheimer’s, and others.

Today, nanoimaging, one such cutting-edge technology, is widely used to structurally characterize subcellular components and cellular molecules such as cholesterol and fatty acids. But it is not without its limitations, as Professor Dae Won Moon of DGIST, lead scientist in a recent groundbreaking study advancing the field, explains: “Most advanced nanoimaging techniques use accelerated electron or ion beams in ultra-high-vacuum environments. To introduce cells into such an environment, one must chemically fix and physically freeze or dry them. But such processes deteriorate the cells’ original molecular composition and distribution.”

“I imagine that our innovative technique can be widely used by many biomedical imaging laboratories for more reliable bioanalyses of cells and eventually for overcoming complex diseases,”

– Prof. Moon

Prof. Moon and his team wanted to find a way to avoid this deterioration. “We wanted to apply advanced nanoimaging techniques in ultra-high-vacuum environments to living cells in solution without any chemical and physical treatment, not even fluorescence staining, to obtain intrinsic biomolecular information that is impossible to obtain using conventional bioimaging techniques,” Dr. Heejin Lim, a key member of the research team, explains. Their novel solution is published in Nature Methods.

Their technique involves placing wet cells on a collagen-coated wet substrate with microholes, which in turn is on top of a cell culture medium reservoir. The cells are then covered with a single layer of graphene. It is the graphene that is expected to protect the cells from desiccation and cell membranes from degradation.

Through optical microscopy, the scientists confirmed that, when prepared this way, the cells remain viable and alive up to ten minutes after placing in an ultra-high-vacuum environment. The scientists also performed nanoimaging, specifically, secondary ion mass spectrometry imaging, in this environment for up to 30 mins. The images they captured within the first ten minutes paint a highly detailed (submicrometer) picture of the true intrinsic distribution of lipids in their native states in the cell membranes; for this duration, the membranes underwent no significant distortion.

With this method too, however, a cascade of ion beam collisions at a point on the graphene film can create a big enough hole for some of the lipid particles to escape. But while this degradation to the cell membrane does occur, it is not significant within the ten-minute window and there is no solution leakage. Further, the graphene molecules react with water molecules to self-repair. So, overall, this is a great way to learn about cell membrane molecules in their native state in high resolution.