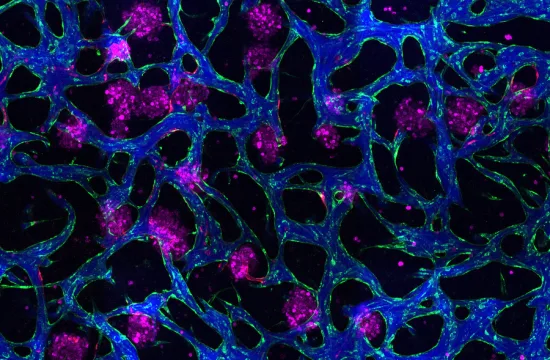

Genome sequences of dinoflagellate algae indicate how they maintain their symbiotic relationship with corals.

Credit : © 2017 Tane Sinclair-Taylor

Advances in genomic research are helping scientists to reveal how corals and algae cooperate to combat environmental stresses. Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) researchers have sequenced and compared the genomes of three strains of Symbiodinium, a member of the dinoflagellate algae family, to show their genomes have several features that promote a prosperous symbiotic relationship with corals [1].

Dinoflagellates are among the most prolific organisms on the planet, forming the basis of the oceanic food chain, and their close symbiotic relationships with corals help maintain healthy reefs. However, because dinoflagellates have unusually large genomes, very few species have been sequenced, leaving the exact nature of their symbiosis with corals elusive.

“We had access to two Symbiodinium genomes, S.minutum and S.kawagutii, and we decided to sequence a third, S. microadriaticum,” said Assistant Professor of Marine Science Manuel Aranda at the University’s Red Sea Research Center, who led the project with his Center colleague Associate Professor of Marine Science Christian Voolstra and colleagues from the University’s Computational Bioscience Research Center and Environmental Epigenetics Program. “This allowed us to compare the three genomes for common and disparate features and functions and hopefully to show how the species evolved to become symbionts to specific corals.”

The unusual makeup of the three Symbiodinium genomes meant that the team had to adjust their software to read the genomes correctly. Ultimately, their research revealed that Symbiodinium has evolved a rich array of bicarbonate and ammonium transporters. These proteins are used to harvest two important nutrients involved in coral-dinoflagellate symbiosis: carbon, which is needed for photosynthesis, and nitrogen, which is essential for growth and proliferation.

Symbiodinium either evolved these transporters in response to symbiosis or the presence of these transporters allowed Symbiodinium to become a symbiont in the first place, noted Aranda.