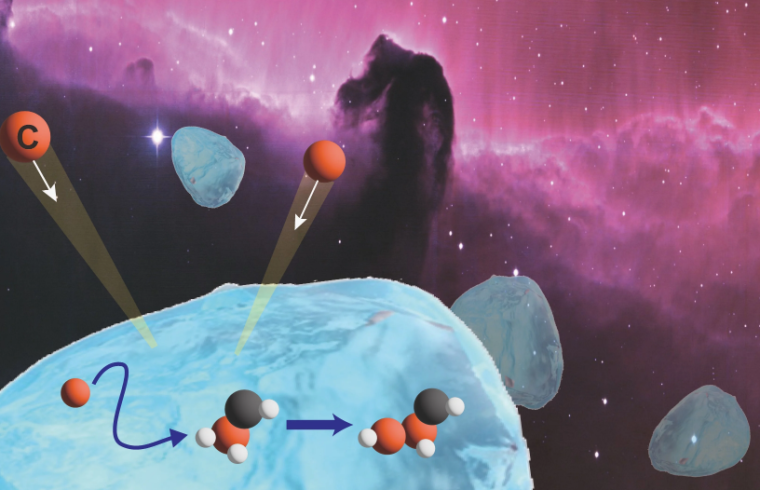

Lab-based studies reveal how carbon atoms diffuse on the surface of interstellar ice grains to form complex organic compounds, crucial to reveal the chemical complexity in the universe.

Uncovering the organic (carbon-based) chemistry in interstellar space is central to understanding the chemistry of the universe in addition to the origin of life on Earth and the possibilities for life elsewhere.

The list of organic molecules detected in space and understanding how they could be interacting is steadily expanding due to ever-improving direct observations. But laboratory experiments unraveling the complex processes can also offer significant clues.

Researchers at Hokkaido University, with colleagues at The University of Tokyo, Japan, report new lab-based insights into the central role of carbon atoms on interstellar ice grains in the journal Nature Astronomy.

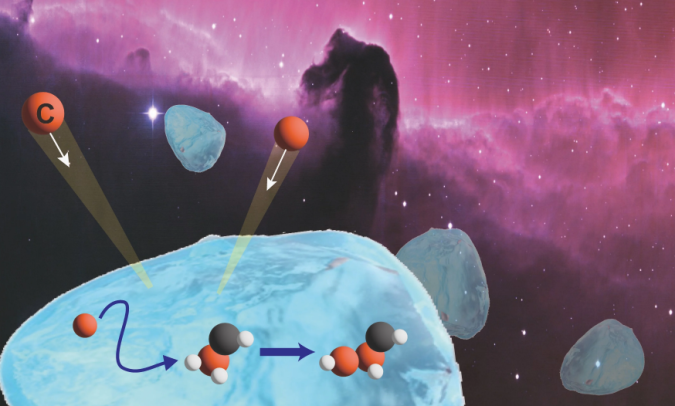

Some of the most complex organic molecules in space are thought to be produced on the surface of interstellar ice gains at very low temperatures. Ice grains that are suitable for this purpose are known to be abundant throughout the universe.

All organic molecules are based on a skeleton of bonded carbon atoms. Most carbon atoms originally formed through nuclear fusion reactions in stars, eventually getting dispersed into interstellar space when the stars died in supernovae explosions. But to form complex organic molecules, the carbon atoms need a mechanism to come together on the surface of the ice grains to encounter partner atoms and form chemical bonds with them. The new research suggests a feasible mechanism.

“In our studies, recreating feasible interstellar conditions in the laboratory, we were able to detect weakly-bound carbon atoms diffusing on the surface of ice grains to react and produce C2 molecules,” says chemist Masashi Tsuge of Hokkaido University’s Institute of Low Temperature Science.

C2is also known as diatomic carbon, a molecule in which two carbon atoms bond together; its formation is concrete evidence for the presence of diffusing carbon atoms on interstellar ice grains.

The research revealed that the diffusion could occur at temperatures above 30 Kelvin (minus 243 °C/minus 405.4 °F), while, in space, the diffusion of carbon atoms could be activated at just 22 Kelvin (minus 251 °C/minus 419.8 °F).

Tsuge says that the findings bring a previously overlooked chemical process into the frame for explaining how more complex organic molecules could be built by the steady addition of carbon atoms. He suggests these processes could occur in the protoplanetary disks around stars, from which planets are formed. The conditions required can also form in so-called translucent clouds, which would eventually evolve into a star forming region. This may also explain the origin of the chemicals that might have seeded life on Earth.

Besides the question of the origin of life, the work adds a fundamental new process to the variety of chemical reactions that could have built, and could still be building, carbon-based chemistry throughout the universe.

The authors also summarize the more general current understanding of the formation of complex organic chemicals in space, and consider how reactions driven by diffusing carbon atoms might modify the current picture.