MIT historian’s new book examines the political value early medieval European kings and nobles found in a royal ritual.

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (MIT News Office)– The Frankish king Charlemagne led armies in battle, united much of medieval Europe under his rule, and was crowned emperor by the pope. Nonetheless, he also had enough time on his hands to become an avid hunter, pursuing deer, wild boars, birds, and other game, often in forests and walled parks near his palaces.

This was no idle hobby. For Charlemagne, hunting had numerous benefits, according to MIT historian Eric Goldberg. For one thing, Charlemagne used the practice to demonstrate his masculine strength into his 60s, after he stopped commanding armies in person. Hunting was also a royal rationale for seizing more wilderness properties and making them royal forests. And it became a common cultural currency, shared by elites across Charlemagne’s sprawling kingdom.

“Charlemagne and his immediate descendants were the first rulers who made hunting a ritual that played a lot of roles in the culture of the kingdom,” Goldberg explains. “It’s about bonding with nobles, and a way of demonstrating the king’s health. … It’s a means of articulating control of territory. It can also be a way the king shows favor to another person.”

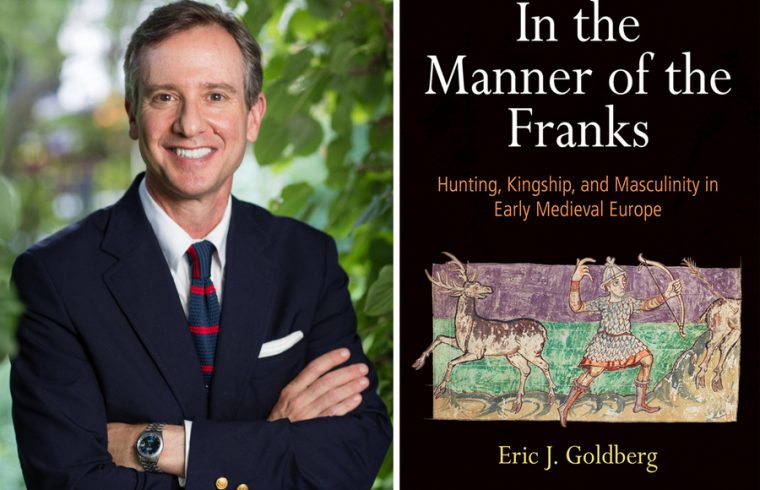

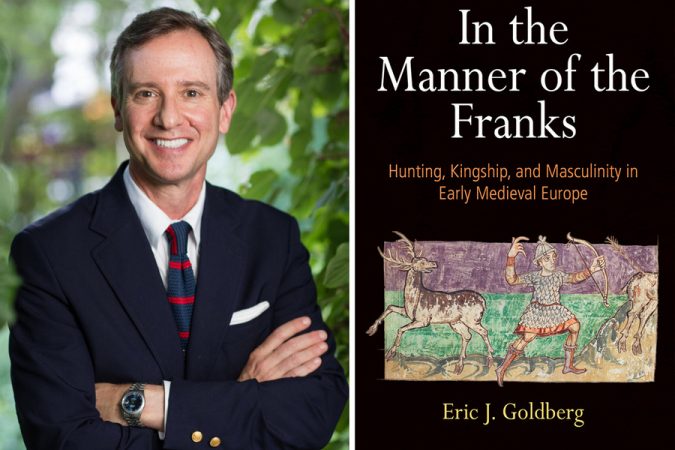

Now Goldberg examines the issue in depth in a new book, “In the Manner of the Franks: Hunting, Kingship, and Masculinity in Early Medieval Europe,” published by the University of Pennsylvania Press. In it, Goldberg details the history of hunting in Europe from about 300 A.D., during the late Roman Empire, until 1000 A.D., scrutinizing how it influenced political, social, and legal relations among people. While shedding light on a very specific subject, the book illuminates broad trends in European history.

“It’s a window into studying political culture and the ruling elites,” Goldberg says while noting that elite culture, in turn, affected much of political life. “The hunt was a spectrum through which to see all society.”

A Roman inheritance

Conventional wisdom holds that hunting only became a prominent aristocratic activity in the 12th and 13th centuries, during the “high” Middle Ages. But as Goldberg emphasizes, early medieval kings and nobles adopted it directly from the Romans. Indeed, in hunting as in other realms of life, the alleged “Dark Ages” featured a significant Roman cultural inheritance, more sophistication, and more variety than is often assumed.

“Hunting in the early Middle Ages actually has a history,” Goldberg says. “It’s not the same thing all the time.” And at first, he notes, “When the Germanic peoples took over the late Roman empire, they were not trying to destroy Roman culture. They wanted to embrace it and be part of it. They wanted to live in villas, drink wine, and go to baths. And hunting was one of those rituals.

“Hunting comes out of late classical culture, and is very important for making aristocratic manhood. It’s a form of military training, teaching equestrianism, archery, use of weapons, courage, patience, discipline, essential things for aristocrats that give them this new identity as the ruling class of the West.”

As for what aristocrats hunted, red deer and wild boar were near the top of the list — but many things were fair game, including brown bears, the fast-moving European hare, the aurochs (a huge, now-extinct kind of wild cattle), and birds; some European nobles were skilled at falconry, using birds of prey to help hunt game. Nobles were not hunting because they needed to, Goldberg notes; they had plenty of food otherwise. Hunting was a luxury pastime and a marker of elite manhood.

Enter Charlemagne

But while hunting was a long-time aristocratic activity, it took on more importance once Charlemagne became king of the Franks, in what is mostly now France, in 768.

“It’s clear early medieval kings were hunting, but it was an elite pastime they were sharing with other aristocrats,” Goldberg says. “It’s only with Charlemagne that for the first time we start getting poets praising the king as a great hunter, or royal legislation dealing with royal forests, and protecting the game within them.”

Roman codes held that game belonged to anyone who could kill it, but Charlemagne changed the law so that any game animals within his (expanding) royal forests belonged to him. There were draconian financial penalties imposed upon commoners who went hunting on the king’s territory — fines so steep they virtually assured enslavement because commoners could seldom afford to pay them.

Meanwhile, Charlemagne soon led his Frankish empire to military victories and an expansion into modern-day Germany, Italy, and beyond — the first time one person had ruled over that much of Europe since the Romans.

“It’s really under Charlemagne and his family that Europe emerges as a clear polity,” Goldberg says. And as Charlemagne expanded his empire, hunting helped link a disparate group of nobles together around the king.

“Europe is a very diverse place,” Goldberg observes. “You have a lot of different languages and legal traditions, but they’re all starting to call themselves Franks. What you see is Charlemagne taking a very diverse empire and forging a new aristocracy, in lots of ways, through legislation, assemblies, standardizing Christianity, but also by giving them this hunting culture. A Bavarian can look an Acquitanian in the eye and see a Frank there, because they are all part of the same culture.”

Casting a wide net

“In the Manner of the Franks” has drawn praise from other medieval scholars. Helmut Reimitz of Princeton University calls it “an excellent and insightful book that will serve as the standard reference work on the hunt for many years.”

To conduct his research, Goldberg looked at a range of historical materials, from early medieval manuscripts and chronicles to royal biographies, laws, decrees, illuminations manuscripts, poetry, art, and archaeological evidence (such as the remains of animal bones, indicating what kind of game people ate).

“It really required an interdisciplinary approach to the evidence,” Goldberg says. “To use a hunting metaphor, I had to cast my net very widely.”

Goldberg also examines a wide range of social issues associated with hunting, including gender roles. There are no documented cases of women hunting; instead they helped preside over the banquets and feasts that would follow.

“Part of it is that hunting was so closely associated with military training, and women did not carry arms or participate in warfare,” Goldberg says. “Surely, somewhere, some women went hunting, but nobody talks about it [in existing documents]. But women did come as spectators, and a ritual associated with hunting is the banquet [after], a very ceremonial part of the hunt. The Queen was essentially in charge of the banquets.”

All told, Goldberg says, by studying hunting, and examining daily life throughout the early medieval period, we see it was a much more lively and ever-shifting era in history than most people realize.

“Traditionally, scholars don’t really know what to do with this period,” Goldberg says. “Edward Gibbon, in the 18th century, felt it is just a melancholy tale of decline and fall. But now medievalists think this is a much more interesting era of transformation, with the emergence of new cultural institutions and practices, and new empires. Decline is not a very helpful way of thinking about it.”