Mental training such as mindfulness meditation – an accepting awareness of the present moment – has been shown to alter networks in the brain and improve emotional and physical well-being. But researchers are still discovering how such practices change the brain and what differences exist between people who meditate regularly and those who do not.

In one of the largest studies of its kind to date, published in the journal NeuroImage, a team of researchers at the Center for Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin–Madison examined brain activity in non-meditators, new meditators, and long-term meditators with thousands of hours of lifetime experience. The researchers discovered differences in emotion networks of the brain among these groups.

“Overall these findings are important because they show that alterations in key brain circuits associated with emotion regulation can be produced by mindfulness meditation,” says Richard Davidson, William James and Vilas Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry at UW–Madison, who led the work. “Some changes can occur in a relatively short time while other changes require much more practice.”

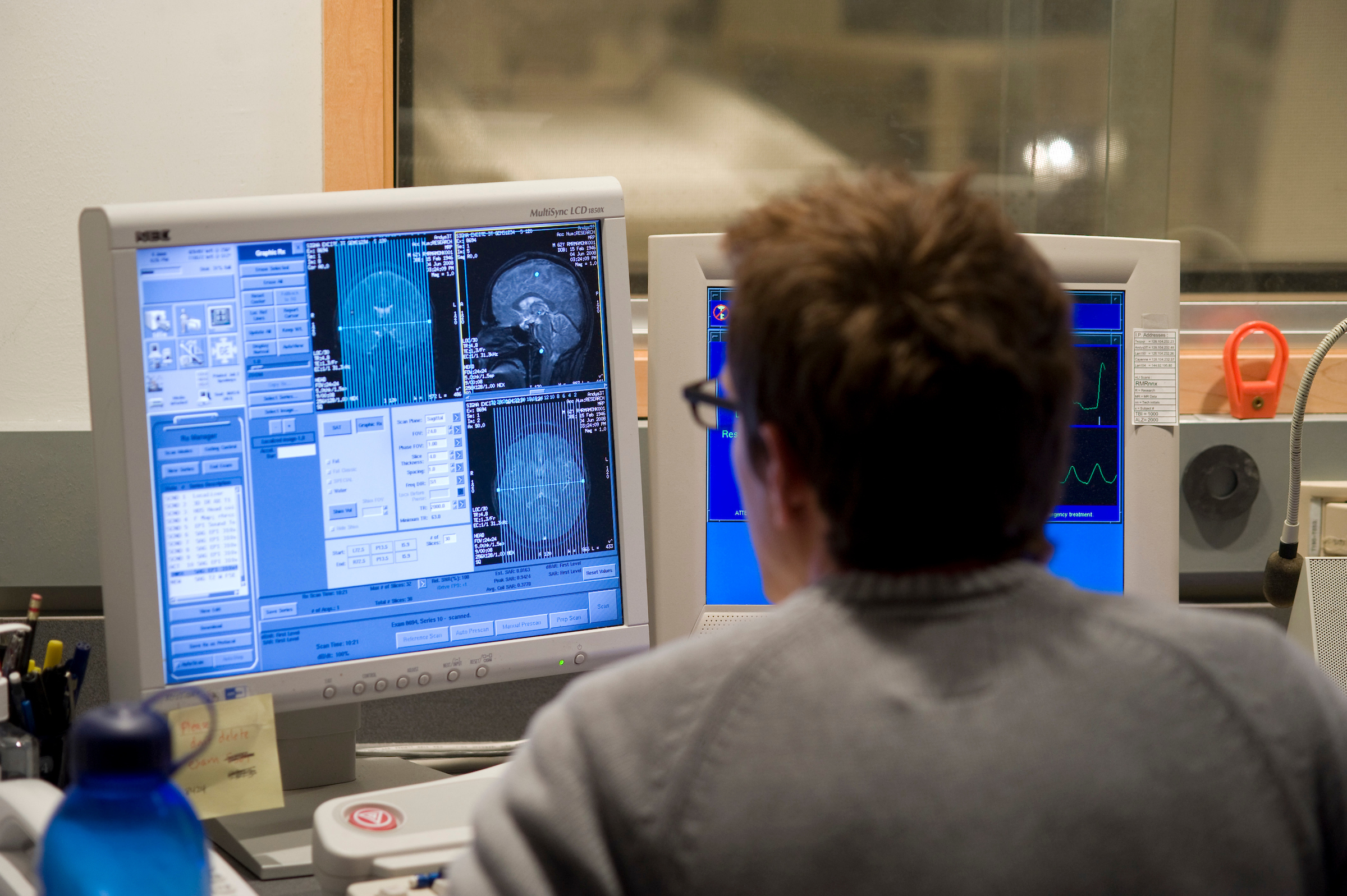

After an eight-week period, participants viewed and labeled photos as either emotionally positive, negative or neutral while undergoing a brain scan by functional magnetic resonance imaging.The study included more than 150 adults. The long-term meditators already practiced daily and had completed multi-day meditation retreats. New meditators were randomly assigned to an eight-week mindfulness-based stress reduction course that included meditation. The control group, made up of people with no meditation experience, was randomly assigned to a “health enhancement program” over the same time period that included well-being practices, but not meditation specifically.

Both long-term practitioners and new meditators – when compared to non-meditators – showed reduced activity in the amygdala when they viewed emotionally-positive images. The amygdala is an area of the brain critical for emotion and detecting important information from the environment.

The researchers also found that more experience with meditation practice on retreat among long-term meditators was associated with reduced activity in their amygdalae when viewing negative images. While reductions in reactivity to positive images were seen with across all levels of training, this indicates that modulating reactivity to negative emotional challenges requires more training.

“These findings are important in demonstrating functional changes in a key circuit underlying emotion regulation after just eight weeks of mindfulness practice,” says Davidson. “They are also sobering in highlighting the fact that alterations in responsivity to challenging negative images occurs only after several thousand hours of practice.”

Mindfulness practices decrease the extent to which emotional stimuli hijack us, the researchers say, and it may simply be that less meditation practice is required to change the brain’s response to positive images than to negative ones.

“The amygdala is not so much about feeling good or positive experience; it’s a salience detector and helps alert us that something important is happening in our environment,” says lead study author Tammi Kral, a graduate student in psychology at UW–Madison. “A heightened response in the amygdala is more linked to grasping or wanting something. So, it makes sense to not have as strong of a response, even in the face of positive stimuli, because equanimity is a goal.”

She adds that lower activity in the amygdala in response to negative images was a general trend across meditators, but was strongest and most significant in long-term meditators with more intense retreat experience.

In addition, the team discovered that, following eight weeks of training, people new to meditation showed an increase in connectivity between the amygdala and an area of the brain that supports executive function (which includes self-regulation and goal tracking) and emotion, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

This was not seen in long-term meditators, perhaps because emotion regulation becomes more automatic with increased practice, the researchers surmise.

Though the team analyzed data from the whole brain to find other differences, the study did not focus on other ways positive emotion may be altered in the brain, including participants’ ability to savor positive emotions, which is known to be among the benefits of these mental training practices.

Because researchers wanted to understand meditation’s impact on a non-clinical population, the study did not include people who took medications for mental health disorders or had a diagnosed psychiatric disorder within the past year. But the team hopes to expand the research in the future to look at a mix of people with and without mental health disorders to see if the findings are similar.

Finding ways to link the brain activity results to how people regulate their emotions in real-life circumstances is another important step in understanding how meditation affects people’s emotional well-being in their daily lives.

The research was made possible by grants from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine grant (P01AT004952) and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH43454).