BY JOHANNES ZUTT | the world Bank

It has been a month since a 7.8 magnitude earthquake hit central Nepal on April 25. What happened next?

Having experienced a real threat of death, many survivors manifested avoidance (“I don’t want to talk about it!”), hyper-vigilance (“What’s that noise? Is the ground moving?”), intrusive thoughts (“What if the next big one may come while I’m asleep …?”) — classic stress reactions.

Many Bank staff have had many sleepless nights as the aftershocks continued, more than 250 to date above a magnitude of 4, thirty above 5, four above 6, and—just when we first thought that life was becoming normal again—a 7.3 on May 12.

That one came like the first one, in the middle of the day, but it felt like an unwelcome nighttime guest, full of foreboding. People ran into the streets screaming, or silly giddy on realizing that they had survived another one—but even more terrified at what would come next. More people died; more buildings collapsed. People who had moved back into their houses moved out again.

At the World Bank country office, colleagues are constantly asking one another how they are, where they are sleeping, how they and their children are coping.

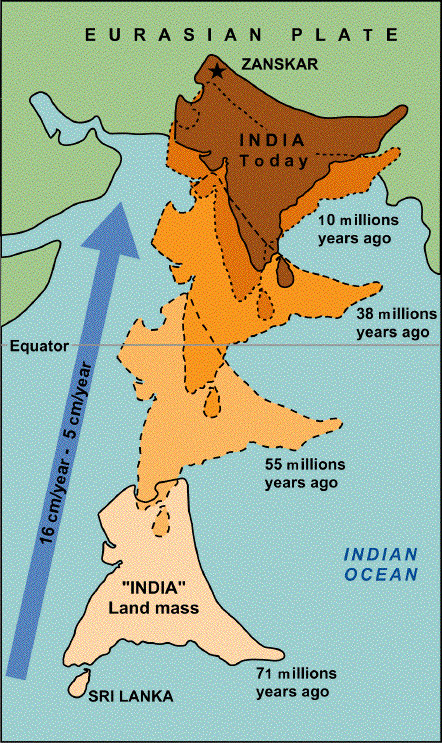

Beneath us, we now know, the Indian plain is moving inexorably northward, sliding under the Tibetan plateau at a rate of 10 to 18 mm per year. Subterranean rock is compressing as it happens, building up more energy that will need to be released in some future earthquake. When? 100 minutes from now? Or 100 years? No one knows. The uncertainty is dreadful.

The 1833 earthquake was well behaved. It knocked, twice: two smaller earthquakes, some hours apart, got everyone out of the house at night, before the big one came. Can’t all of them be so civilized?

Well, no. No one knows when geological time will spring a surprise on human time. But we do know that earthquakes will keep surprising us in the Himalayas, as the great tectonic plates below us continue to collide.

“One day”, says Roger Bilham, a seismologist based at the University of Colorado—“one day hundreds of millions of years from now, India will have disappeared under the Tibetan plateau, and billions of people will be crowded on the Terai, some enjoying beachfront properties.”

Meanwhile, in human time, the world beyond Nepal has moved on. The international media have shifted their attention from the Nepal earthquake to a possible Grexit, Eurovision, the boat people on the Andaman Sea, the latest exploits of the Islamic State, ….

The international search and rescue teams have left Nepal, though relief efforts continue. Supplies are brought by the government, by the UN and various donors, and by armies of private volunteers. The effort is penetrating deeper and deeper into the mountains, to villages and hamlets that have not previously been reached. Trucks carry emergency supplies to the end of a perilous mountain road; motorcycles bring them some miles further on dirt trails; and then people come from the remotest places to pick them up—in huge packs—and carry them on their backs as they hike as many as ten hours more to reach their homes.

Some people are also beginning to work on reconstruction. As the relief workers leave, the reconstruction experts arrive. This was a disaster. People need help to rebuild and resume their normal lives. And small groups of international workers, who had been through similar disasters in the past, were eager to provide whatever help they could. [End part 1]