MADISON – In March, as coronavirus cases spread across the country, University of Wisconsin-Madison engineers responded with a simple design for a medical face shield made from common materials that 450 manufacturers put into production.

The team that developed the Badger Shield in a flash to meet the needs of hospitals, nursing homes and schools has created a new version – again working with partners from UW Health, Midwest Prototyping and others – a shield that provides a full, clear view of the face while still filtering virus particles through surgical fabric that cinches around the wearer’s chin and jawline.

They’re also perfecting a compact, lightweight 3D-printed air-circulation unit for the new shield that prevents it from steaming up or becoming too stuffy. According to Lennon Rodgers, director of the Grainger Engineering Design Innovation Laboratory, the engineering makerspace at UW-Madison, Badger Shield+ was as popular as the original shortly after its debut.

“In just a few days there were requests for 22,000 shields from 348 different organizations from 44 states,” he says.

Rodgers and colleague Karl Williamson designed Badger Shield+ in close collaboration with Nathan Wilke of UW Health and Brian Ellison from Midwest Prototyping, incorporating research on particle-filtering fabrics conducted by David Rothamer, a mechanical engineering professor at UW-Madison.

Midwest Prototyping is fulfilling orders for the Badger Shield+; however, as is the case for its predecessor, Rodgers says the team also plans to make the new version available to manufacturers as open-source design drawings.

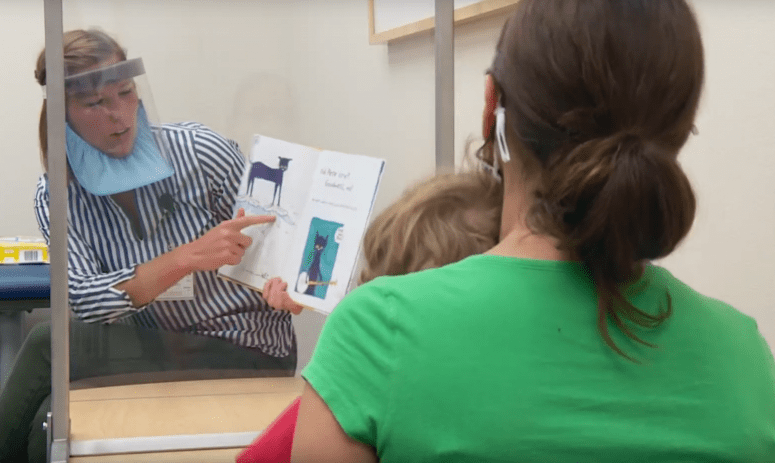

UW Health is continuing to test the shield with several healthcare practitioners, including speech and language pathologists and sign language interpreters, says Wilke, who works with the UW Hospital and Clinics supply chain division.

“Our clinical team is currently required to wear both a face shield and a barrier mask during their work,” Wilke says. “The wearing of the mask, covering the nose and mouth, have made it difficult, if not impossible, for some staff to perform their duties. There are some products on the market to deal with this situation; however, supplies are extremely limited, and delivery times were months away. As a result, we created the hybrid Badger Shield+ integrated barrier mask with the goal to provide comparable clinical protection to a barrier mask and face shield, while allowing patients and families to see the face of the wearer.”

Beyond healthcare, the Badger Shield+ can meet many needs in settings that include schools, daycare facilities, churches and personal uses. Rodgers says schools, many now considering the looming beginning of fall classes, made up 70 percent of those early requests.

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, the team focused on ensuring healthcare professionals had enough personal protective equipment. This time, with the Badger Shield+, Rodgers and Williamson developed a design that met the UW Health requirements, but also broadened its usefulness.

“Karl and I started working on this two months ago when we saw this wave of public openings,” says Rodgers. “We were starting to think outside the box for PPE that didn’t exist. Most PPE is designed for hospitals; we wanted PPE that members of the public could use as they went about their lives. It’s well suited for schools, and for people who need others to see their mouth or need an alternative PPE solution for various reasons. “

Leveraging the makerspace’s prototyping resources, including 3D scanning, laser cutting, 3D printing and sewing, Badger Shield+ builds on the simple design of the original face shield. However, says Rodgers, because it’s a new concept, the latest version evolved over time, thanks to critiques from UW Health clinicians.

“It took six or seven iterations-where does the fabric come up to, where does the drawstring go, and so on,” says Rodgers. “Karl sent a really organized set of options and the clinicians would mark them up to note improvements. We found out that people wanted simple and lightweight.”

Approximately 40 UW Health clinicians and staff helped evaluate the Badger Shield+ designs, says Wilke, who facilitated that feedback.

“The current version features an anti-fog plastic lens, which has helped address an issue identified early in the development,” he says. “Another design element that required some iteration included the use of a cinching strap along the chin and neck area, which was approved by our safety and risk management teams.”

Air Assist, a quiet, lightweight, 3D-printed air-circulation disc that anchors to the fabric portion of Badger Shield+ with the help of a thin ring of magnets, is close to being ready, also.

“The ‘Ah, ha!’ moment for it came a couple of months ago,” says Rodgers. “We were all wearing masks, and we were hot. This provides a small level of circulation and prevents the Badger Shield+ from feeling stuffy.”

He says the Badger Shield+, coupled with (or without) the air circulation unit, could be a low-cost alternative for people who might not otherwise have been able to wear a traditional cloth mask. Rodgers also is working on his campus on a variety of options designed to help keep UW-Madison instructors safe as they plan in-person teaching for fall 2020 and beyond.