Researchers have identified a second path to defeating chronic myelogenous leukemia, which tends to affect older adults, even in the face of resistance to existing drugs.

The new findings were published on September 17th in Nature Communications.

Almost all patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia, or CML, have a faulty, cancer-causing gene, or “oncogene” called BCR-ABL1. BCR-ABL1 turns a regular stem cell in the bone marrow into a CML stem cell that produces malformed blood cells. And instead of the CML stem cell dying when it should be scheduled to do so, the oncogene causes it to keep producing even more of these faulty blood cells.

Advances in treatment since the turn of the millennium have been extremely successful at combatting the disease in patients with this oncogene.

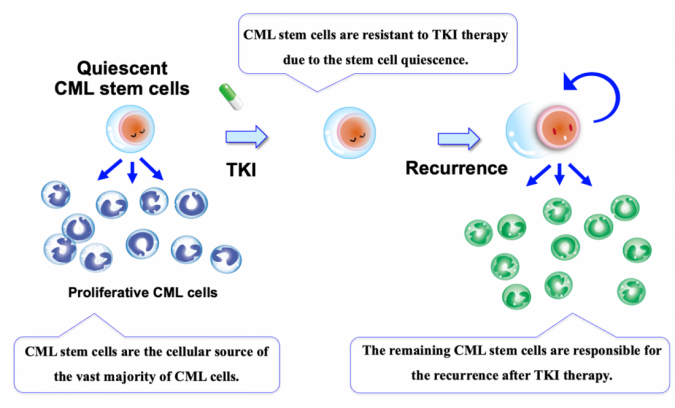

Drugs called tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) have completely transformed the prognosis of people with such leukemias, and with fewer of the side effects of other cancer treatments. In most cases, the cancer goes into remission and patients live for many years following diagnosis.

BCR-ABL1 directs the production of an abnormal type of tyrosine kinase, an enzyme that ‘turns on’ many types of proteins through a cascade of chemical reactions known as signal transduction—in effect communication via chemistry.

Miscommunication resulting from the faulty enzyme is what promotes the growth of the leukemic cells. By stopping this communication within CML stem cells, TKI signal transduction therapy inhibits their growth and brings a halt to their production of the malformed blood cells.

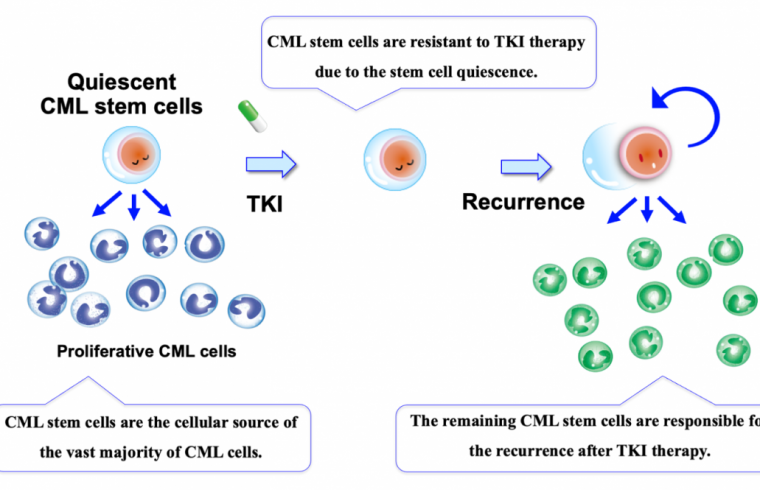

However, TKIs only controls the disease; they don’t cure it. Drug resistance can develop in a patient because while TKIs work well on proliferative mature CML cells that are actively reproducing, they are less effective at inducing cell death on the part of CML stem cells that are quiescent.

Quiescence is an “idling” stage in the life cycle of a cell in which it basically just rests and hangs out for extended periods of time in anticipation of reactivation, neither replicating nor dying.

“If CML stem cells are in a quiescent phase, they are otherwise left untouched by TKI treatment, and so survive to potentially cause a relapse,” said Kazuhito Naka, paper author and an associate professor from the Department of Stem Cell Biology of Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine.

But the researchers found in mouse models that if they disrupt Gdpd3—a different, non-oncogene gene—then the self-renewal capacity of the CML stem cells is sharply decreased. Gdpd3 directs the production of an enzyme for a particular type of lipid that appears to play a key role in regulating the quiescence of CML stem cells in an oncogene-independent fashion.

In other words, the Gdpd3 gene involved in production of this lipid is largely responsible for the maintenance of CML stem cells. The researchers had broken their quiescence.

Crucially, when the researchers disrupted the Gdpd3 gene encoding these lipids, leukemia relapse in the mice was significantly reduced, even when the BCR-ABL1 oncogene was not disrupted.

“This potentially provides another path to arresting these leukemias—and maybe other cancers too,” said Dr. Naka, “beyond having to wrestle with the BCR-ABL1 oncogene.”

While the researchers have discovered a new, biologically significant role for this particular lipid in causing the recurrence of CML, they still do not fully understand the precise way this happens.

The researchers now want to investigate the mechanisms involved and whether this lipid also plays a role in the quiescence of the cancer stem cells that cause solid tumors, not just in leukemias, and thus in these cancers’ recurrence and growth as well. Provided by AsiaResearchNews