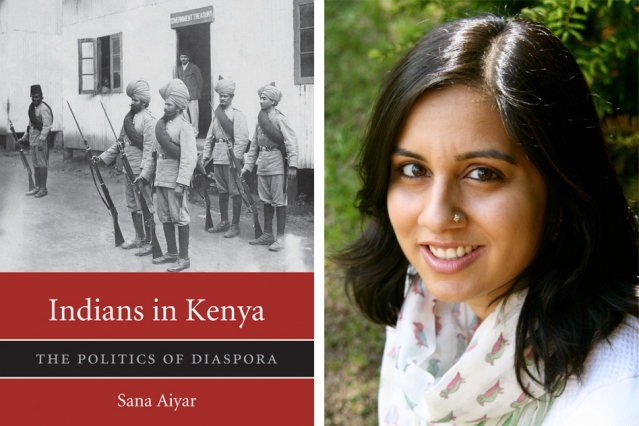

New book details how Kenya’s Indian immigrants established a foothold in a foreign land.

Photo courtesy of Roohia Sidhu Klein

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — They came across the ocean to build railways and work as traders. They settled as merchants, farmers, and government workers, and have stayed for generations. It’s a familiar immigration story, but in this case it concerns a largely unfamiliar group: the Indians of Kenya, who the novelist Shiva Naipaul once described as having “an odd kind of invisibility.”

Traders from present-day India — as well as parts of South Asia that are now in Pakistan — had been sailing across the Indian Ocean to East Africa for centuries. But after Britain took control of Kenya in 1895, many more Indians, already subjects of the British Empire, began migrating there. By 1963, about 35 percent of the population of Nairobi was of Indian heritage.

“It’s this hidden history that has not been uncovered,” says Sana Aiyar, an assistant professor of history at MIT. “Yes, there’s an imprint of South Asia and Indians in Nairobi, but you don’t think of Kenya as an Indian country.”

It is a fraught history as well, since Kenya’s Indian immigrants existed for years in a kind of political and social limbo: They were generally more upwardly mobile than other Kenyans, but lacked the opportunity for full political participation under British rule. At times, Indians benefitted from British rule, but at other moments, such as during the Mau Mau rebellion of the 1950s, many Indians sided with Kenyans against the British.

Now Aiyar has written a book about this saga — “Indians in Kenya: The Politics of Diaspora,” being published this month by Harvard University Press — which illuminates these social tensions and political changes.

“I think what makes the Indians in Kenya a very interesting case study is that people think about colonialism as having a clear-cut colonizer and colonized,” Aiyar says. “But the Indians really complicate that notion.”

Network effect

Perhaps the first thing to realize about the unlikely success of Kenya’s Indian immigrants is that many of them — about 30,000 — came across the ocean as indentured laborers who had to work their way to freedom. About two-thirds of indentured laborers eventually returned to India. But many of those who stayed became skilled workers on the railways, while others who migrated to Kenya as traders became successful entrepreneurs, often as importers, exporters, or shopkeepers.

“Because there was this pre-existing network of traders, there was no hindrance to them setting up shop,” Aiyar explains. “Within five years they could go from being someone who’s just exploring what the options are, to setting up these big firms. They were very successful, very quickly.”

Among the most successful was Alibhai Mulla Jeevanjee, an Indian trader who entered Kenya around 1890 and became rich, in part, through the construction of a railway linking Kenya with Uganda. Jevanjee became a leading voice for Indian rights in Africa — and straddled the line between colonizer and colonized. As Aiyar writes, Jeevanjee’s claims were in the language of an “imperialist discourse that characterized Africa as an uncivilized and savage land” — one that Indians were taming through commerce.

Yet the British continually resisted the claims to greater political power by Jeevanjee and other Kenyan Indians. That helped the empire retain its immediate hold on the country, but alienated Indians in the long run.

“It was a strategic miscalculation,” Aiyar says. “[The British] got very aggressive about saying, ‘Let’s not let Indians into the legislative process.’”

Caught in between

By the time of Kenya’s Mau Mau rebellion, which lasted through most of the 1950s, the political sympathies of Kenya’s Indian community had fractured, largely along generational lines. Some prominent older Indians in Kenya opposed the rebels; many younger, educated Kenyans of Indian heritage opposed the British response.

Afterward, liberation politics again threatened the Indian community’s sense of belonging; some visions of independence in Kenya, emphasizing ethnic nationalism, also left little room for Indians. In response, many Indian arguments for participation in an independent Kenya, Aiyar notes, cited economic necessity, claiming that “Indian capital was needed for the state to be viable.”

Kenyan independence in 1963 was followed by a tense decade for the country’s Indians: Many emigrated to Britain, but roughly 100,000 stayed, remaining relatively prosperous.

Aiyar says that for all the emphasis by Kenya’s Indians regarding their economic utility to the state, her research underscores their deep feeling of belonging in Kenya — mixed with a strong notion of Indian heritage.

“There is this sense in which the diaspora really feels it belongs to Kenya,” Aiyar observes. “Kenya has been their territorial homeland. There is a civilizational homeland of India, but their desire to stay in Kenya is much more than just a strategic move.”