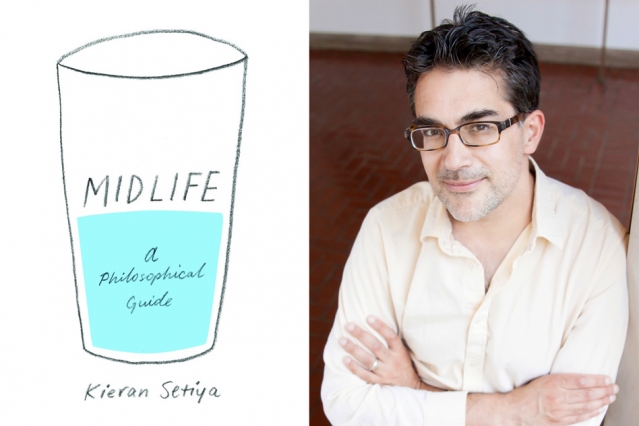

MIT professor Kieran Setiya’s book “Midlife” aims to smooth out the rocky road of middle age.

Photo: Courtesy of Kieran Setiya

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — A few years ago, a man experienced a midlife crisis. He was professionally successful and had a rewarding family life, but still had a “hollow” feeling. Could he grind away at the same job indefinitely? Would he have to abandon his older hopes and dreams? And wasn’t it disheartening to think his life might be halfway over?

Fortunately, this person didn’t quit his job, blow his life’s savings on sports cars, or sabotage his personal relationships. Instead, he went to his office and pondered matters.

“I was doing the things I had always wanted,” explains MIT philosophy professor Kieran Setiya, the fellow suffering through the midlife malaise. “I wasn’t wrong to think that teaching and writing and thinking about philosophy was worth doing, but nevertheless, something was amiss. The thing that gripped me first was a sense of hollowness in pursuit of projects. You can be aiming to get things done and have an absence of satisfaction.”

Then again, existential doubt in midlife can have other sources. “There are many midlife crises,” Setiya acknowledges. “There’s a sense of constraint and limitation and regret. Death is closer.”

Now Setiya has woven these strands into a new book, “Midlife: A Philosophical Guide,” published by Princeton University Press. In it, he examines the problems of middle-aged happiness, reaches some unusual conclusions — he thinks we should embrace our regrets — and explores how philosophy can help people find peace of mind.

Indeed, “Midlife” has a clear prescription for living well. Setiya believes “atelic” activities — things we enjoy for their own sake — make us fulfilled. Too often, he states, we are consumed with “telic” activities: goal-driven projects that leave us unsatisfied in the present. (The terms derive from “telos,” the Greek word for “goal.”)

“What really matters is that some important things in your life, things you regard as sources of meaning, are atelic,” Setiya says. “Reading, or walking, or thinking about philosophy, or parenting, or spending time with your friends or family are activities that don’t have an endpoint built in. There isn’t a sense that in doing it you’re exhausting it, as if you could complete the project of hanging out with your friends.”

Trust the process

As Setiya chronicles in the new book, the concept of the midlife crisis did not really develop until the 1960s, and it has largely been the province of psychologists, not philosophers. Still, writings about the middle stage of life extend back to ancient times, and two famous 19th-century philosophers figure prominently in Setiya’s book: John Stuart Mill and Arthur Schopenhauer.

Both Mill and Schopenhauer questioned the project-driven life, with Schopenhauer arriving at the bleak conclusion that a life of finite goals would leave us perpetually reliving the past or focused on the future, but never satisfied in the present.

“I think Schopenauer missed or didn’t see the value of atelic activities — the process, not the project,” Setiya says.

But as Setiya notes, designing your life purely around atelic activities isn’t realistic either. Most of us cannot indulge in endless hobbies: “When the demands of life are pressing, too urgent to be ignored, it would be a mistake to devote all day to contemplation, reading Wordsworth, or playing golf,” Setiya writes in the book.

Moreover, the distinction between atelic and telic activities is not total. A goal-oriented project can still be intrinsically fun — think of a teacher who helps students learn certain things but aims for everyone to enjoy the classroom. That experience is both atelic and telic.

“Most of the things you’ll be doing at any given time will be describable in both ways,” Setiya agrees. “You don’t necessarily need to shift what you’re doing, but just try to find the atelic in it, and find the value in that. I’m not going to stop writing philosophy articles, but the point is to be doing philosophy, not just to get the article done.”

Why you should embrace regret

More provocatively, Setiya contends in the book that the perceived narrowing of life’s possibilities, often a big part of the midlife crisis, should be regarded as a good thing, not a source of regret.

True, most of us will never become movie stars or famous athletes or try all the careers we once found intriguing. We will never visit all the places we want to see or befriend everyone we wanted to know better. However, Setiya suggests, this is just “a recognition of the richness of valuable things in the world.” Feeling regret in this sense is better than feeling nothing.

Or, as Setiya elaborates: “It’s tempting to complain about how even when things go well, there are all kinds of things you’ll never do. But there is a certain consolation in thinking why that is. It’s because the world offers up many different things worth doing and worth wanting. And it’s true you can’t do all of them. But to live a life where you don’t miss out, you’d have to be utterly blinkered, and narrow your focus so much there’s only one thing you care about. And that really isn’t a preferable life.”

In this vein, Setiya cites Plato’s observation in the “Philebus,” that to live with no unsatisfied wishes, “You would thus not live a human life, but the life of a mollusk or of one of those creatures in shells that live in the sea.”

U can make the U-turn

Not every chapter of “Midlife” offers clear consolations. After weighing various philosophical arguments that we should not fear death, Setiya concludes that our concerns about it are, in logical terms, well-founded. On the bright side, he also emphasizes recent psychological research indicating that the midlife crisis is not an irreversible change, but a temporary phase.

Happiness often follows a U-curve in which middle age is uniquely stressful, with a heavy dose of responsibilities. That’s all the more reason to seek out atelic activities when the midlife blues hit: meditation, music, running, or almost anything that brings inner peace. But self-reported happiness does increase later in life.

Oddly, as Setiya observes, many of the most consequential choices we make occur in our 20s and early 30s: careers, partners, families, and more. The midlife crisis is a delayed reaction, hitting when we feel more weighted down by those choices. So the challenge is not necessarily to change everything, he says, but to ask, “How do I appreciate properly what I now am doing?”

In this sense, Setiya believes, “Midlife” is about middle age, but middle age just represents a more acute stage of existential insecurity that is always present.

“The book is about midlife in the sense of how to cope with being in the middle of this constantly ongoing process of life, that involves a past that you have to deal with, a future that’s getting shorter, and projects that get completed and replaced,” Setiya says. “I hope it will be of use to a wider range of people than just 40- or 50-somethings.”