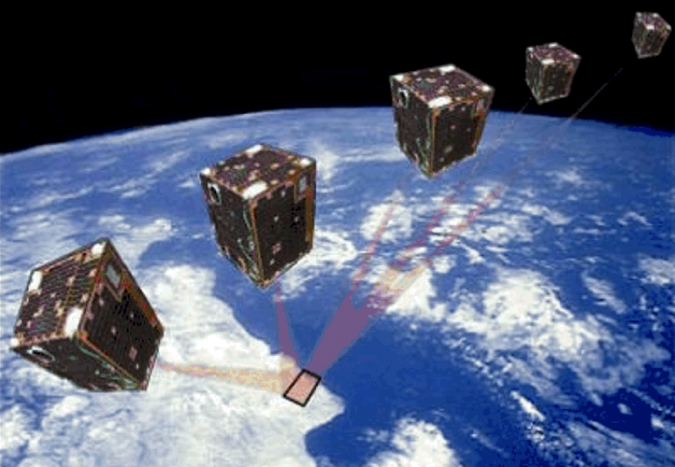

On 22nd October, twenty years ago, first small satellite, Proba-1 (Project for On-Board Autonomy), was launched by European Space Agency (ESA) with just one goal – to prove technologies in space.

But, once in orbit, that same small satellite quickly proved to be not so little in its capabilities.

Today, twenty years on Proba-1, which was intended to survive just two years, is still going strong as an Earth Observation mission and its legacy is already future-proofed into the next decade.

Measuring just 60 x 60 x 80 cm, Proba-1 autonomoulsy performs advanced guidance, navigation, and control processing, as well as payload resources management. Its two imaging instruments – the Compact High-Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (CHRIS) and the panchromatic High-Resolution Camera (HRC) – have provided more than 1000 images of more than 1000 sites.

The images have been vital for monitoring several environmental concerns, from assessing how different lad use strategies in Namibian savannah as affect the vegetation growth, to on vegetation types in Central Nambia’s savannahs, or helping to map and understand alpine snow cover in Swiss National Parks.

The micro-satellite was developed by ESA’s General Support Technology Programme (GSTP) and built by an industrial consortium led by the Belgian company Verhaert.

Proba-1 marked a change towards small missions in European space industry. While CubeSats and are more and more common and available these days, Proba 1 was ESA’s first venture into small missions. The mission was developed in just three years – an unheard-of feat at the time when missions often took more than 10 years to launch. It also marked the beginning of a series of Proba satellites, including Proba-2, Proba-V and the currently-in-testing Proba-3,

“In its time, it was completely innovative,” reminisces Frederic Teston, the Project Manager for Proba. “In terms of the technology, in terms of the development time, in terms of the low cost – it was all brand new.”

In twenty years, none of the primary units have actually failed and the spacecraft remains operational on all primary systems at this time. The satellite fulfilled many firsts for ESA – from being the first to use a lithium-ion battery (now an ubiquitous technology) to being the first ESA spacecraft with fully autonomous capabilities.

This meant it was designed to perform virtually unaided, running everyday tasks like navigation, payload, and resource management with little involvement by staff at ESA’s ground station in Redu, Belgium.