Sea discoloration data obtained from satellite images as a novel criterion in predicting if eruption looms for an underwater volcano, according to new new study.

There have been frequent eruptions of submarine volcanoes in recent years. The past two years alone recorded the explosions of Anak Krakatau in Indonesia, White Island in New Zealand, and Nishinoshima Island in Japan. Observing signs of volcanic unrest is crucial in providing life-saving information and ensuring that air and maritime travel are safe in the area.

Although predicting when a volcano will erupt can be difficult as each behaves differently, scientists are on the lookout for these telltale signs: heightened seismic activity, expansion of magma pools, increases in volcanic gas release, and temperature rises.

For submarine volcanoes, Yuji Sakuno, remote sensing specialist and associate professor at Hiroshima University’s Graduate School of Advanced Science and Engineering, proposed a new indicator — sea color.

The relationship between the chemical composition of discolored seawater and volcanic activity has been known for a long time. Still, there have been very few quantitative studies that used remote sensing to explore it. And among these few studies, only the reflectance pattern of discolored seawater has been analyzed.

“This is an extremely challenging research result for predicting volcanic disasters that have frequently occurred in various parts of the world in recent years using a new index called sea color,” Sakuno said.

“I was the first in the world to propose the relationship between the sea color information obtained from satellites and the chemical composition around submarine volcanoes.”

Sakuno explained that volcanoes release chemicals depending on their activity, and these can change the color of the surrounding water. A higher proportion of iron can cause a yellow or brown discoloration, while increased aluminum or silicon can stain the water with white splotches.

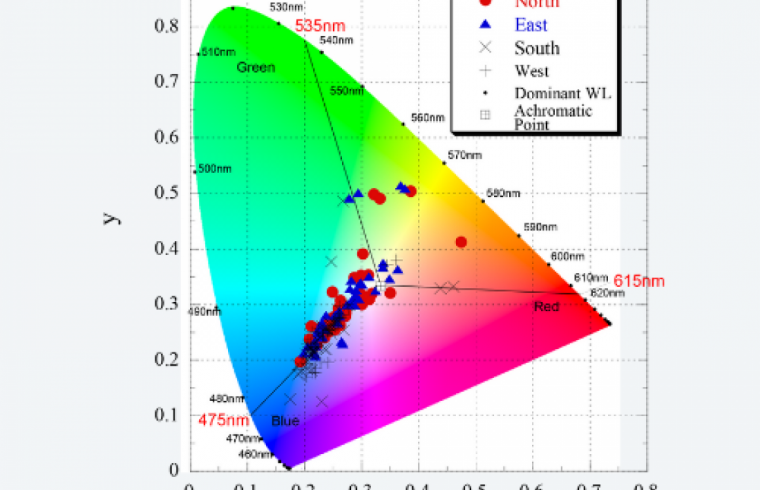

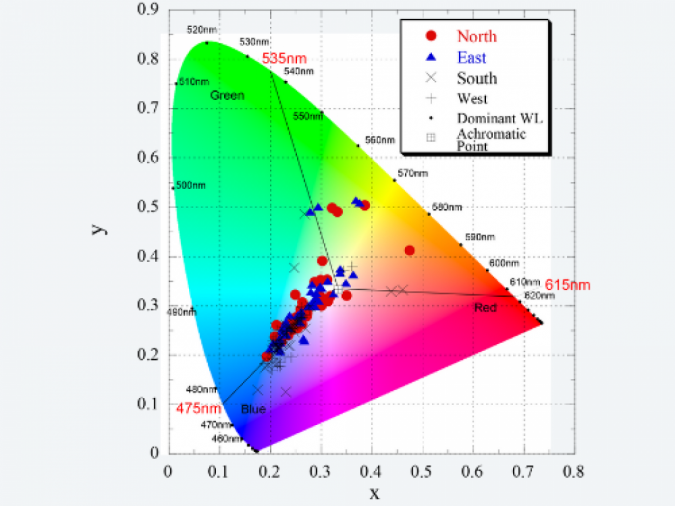

One problem, however, is that sunlight can also play tricks on sea color. The study looked at how past research that chromatically analyzed hot spring water overcame this hurdle and fixed brightness issues. A relational model between seawater color and chemical composition was developed using the XYZ colorimetric system.

Sakuno examined images of Nishinoshima Island captured last year by Japan’s GCOM-C SGLI and Himawari-8 satellites. Himawari-8 was used to observe volcanic activity and GCOM-C SGLI to get sea color data. GCOM-C SGLI’s short observation cycle — it takes pictures of the ocean every 2-3 days — and high spatial resolution of 250 m makes it an ideal choice for monitoring.

Using the new indicator, Sakuno checked satellite data from January to December 2020 and was able to pick up signs of looming volcanic unrest in Nishinoshima Island approximately a month before it even started.

“In the future, I would like to establish a system that can predict volcanic eruptions with higher accuracy in cooperation with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the Maritime Security Agency, which is monitoring submarine volcanoes, and related research,” he said.

The findings of the study are published in the April 2021 issue of the journal Water.