Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have discovered a protein that fine-tunes the cellular clock involved in aging.

This novel protein, named TZAP, binds the ends of chromosomes and determines how long telomeres, the segments of DNA that protect chromosome ends, can be. Understanding telomere length is crucial because telomeres set the lifespan of cells in the body, dictating critical processes such as aging and the incidence of cancer.

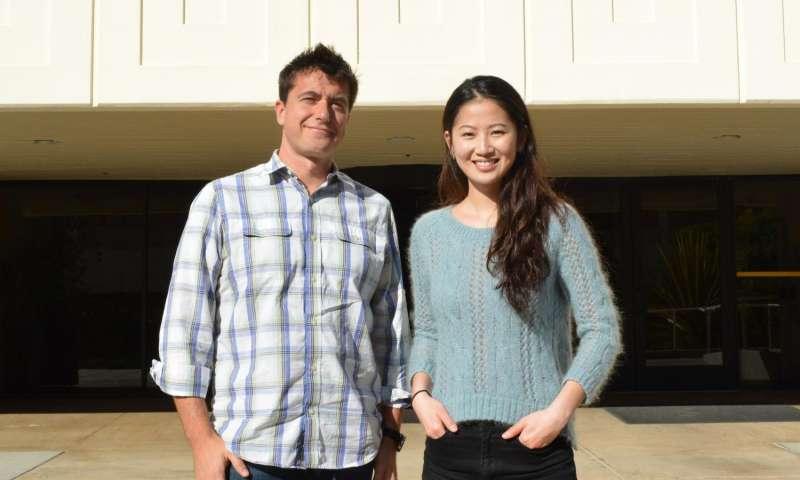

“Telomeres represent the clock of a cell,” said TSRI Associate Professor Eros Lazzerini Denchi, corresponding author of the new study, published online today in the journal Science. “You are born with telomeres of a certain length, and every time a cell divides, it loses a little bit of the telomere. Once the telomere is too short, the cell cannot divide anymore.”

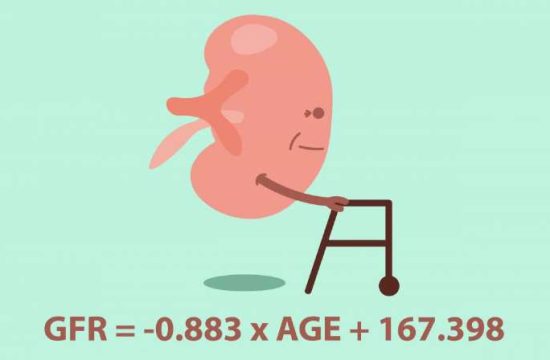

Naturally, researchers are curious whether lengthening telomeres could slow aging, and many scientists have looked into using a specialized enzyme called telomerase to “fine-tune” the biological clock. One drawback they’ve discovered is that unnaturally long telomeres are a risk factor in developing cancer.

“This cellular clock needs to be finely tuned to allow sufficient cell divisions to develop differentiated tissues and maintain renewable tissues in our body and, at the same time, to limit the proliferation of cancerous cells,” said Lazzerini Denchi.

In this new study, the researcher found that TZAP controls a process called telomere trimming, ensuring that telomeres do not become too long.

“This protein sets the upper limit of telomere length,” added Lazzerini Denchi. “This allows cells to proliferate—but not too much.”

For the last few decades, the only proteins known to specifically bind telomeres is the telomerase enzyme and a protein complex known as the Shelterin complex. The discovery TZAP, which binds specifically to telomeres, was a surprise since many scientists in the field believed there were no additional proteins binding to telomeres.

“There is a protein complex that was found to localize specifically at chromosome ends, but since its discovery, no protein has been shown to specifically localize to telomeres,” said study first author Julia Su Zhou Li, a graduate student in the Lazzerini Denchi lab.

“This study opens up a lot of new and exciting questions,” said Lazzerini Denchi.

Source: dddmag.com