Researchers in Japan and Russia have found some snail species that counterattack predators by swinging their shells, suggesting the importance of predator-prey interactions in animal evolution.

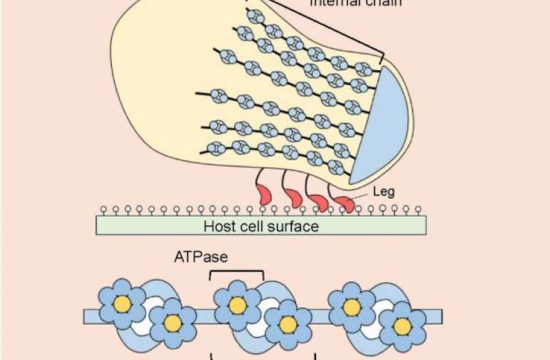

Until now, snails were thought to protectively withdraw into their shells when attacked. However, an international research team has found a pair of snail species that use their shells like a club to hit predators and knock them over.

Evolutionary scientists have been questioning how predator-prey interactions affect the evolution of the prey. However, they are yet to resolve whether this interaction induces the diversification of the prey species and its morphological features and behaviours, and if so, why?

Researchers from Japan’s Hokkaido University and Tohoku University collaborated with colleagues at the Russian Academy of Sciences to closely study snail species from the genus Karaftohelix in both countries. They observed each species’ defensive behaviours against their predator, the carabid beetle, and conducted shell measurements and species comparisons. The team used DNA sequencing to analyse how closely related the species were to each other.

[pullquote]By analysing DNA sequences of each species, the team also discovered that the two active-or-passive defensive methods evolved independently in the Japanese and Russian species. [/pullquote]

They found that two snail species—Karaftohelix (Ezohelix) gainesi in Hokkaido, Japan and Karaftohelix selskii in the Far East region of Russia—swing their shells to hit the carabid beetles, demonstrating a very unique, active defence strategy; while other closely related snail species withdraw their soft bodies into their shells and wait until the opponent stops attacking. “The difference in their defensive behaviours is also reflected in their shell morphology, indicating that their behaviours and shell shapes are interrelated to optimize the preferred defence strategy,” says Yuta Morii, the study’s lead author.

By analysing DNA sequences of each species, the team also discovered that the two active-or-passive defensive methods evolved independently in the Japanese and Russian species.

Their findings suggest that the selection of each method has led to the diversification of the behaviours, shapes and species of the snails. This study, published in the Journal Scientific Reports, is one of only a few to report on land snails using their shells for active defence by swinging them against a predator.

“Our study showcases the importance of predator-prey interactions along with resource competition as major selective forces affecting the evolution of morphological and behavioural traits in organisms,” Morii adds.