A recent study conducted by Lingnan University and the University of Oxford proposes finds that university graduates retain rewards despite their diminishing scarcity as long as they possess good cognitive skills.

Scholars and policymakers have long used credential inflation theory to explain the devaluation of university degrees as the consequence of the oversupply of tertiary-educated personnel as compared to the labour demand in the world of work.

According to credential inflation theory, the link between educational credentials and economic rewards weakens as educational opportunities spread in a society. However, a recent study conducted by Lingnan University in Hong Kong (LU) and the University of Oxford in the UK proposes a new theory of “decredentialization” whereby degree holders lose their economic return only when they are unaccompanied by adequate cognitive skills.

The study finds that credential inflation operates as lower-level (short-cycle) tertiary education expands but that “decrentialization” emerges in tandem with higher-level (bachelor’s and above) tertiary expansion, such that university graduates retain rewards despite their diminishing scarcity as long as they possess good cognitive skills.

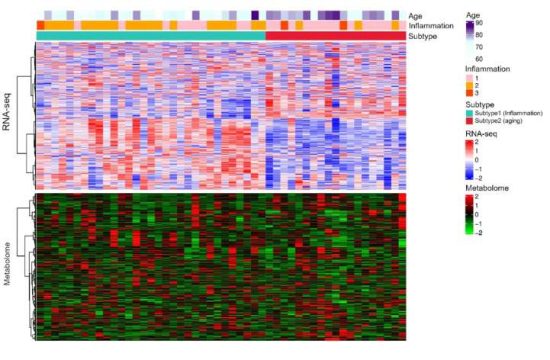

The research team used the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) data for 91,217 individuals from 26 countries between 2011 and 2015 (Figure 1), which supports comparative analyses of the association between educational attainment, skills, and labour market outcomes. The team conducted a cross-sectional multilevel analysis with PIAAC data and other country-level data.

The results show that, as a general tendency, individuals with higher-level degrees are more likely to enjoy economic returns, followed by lower-level degree holders, and then highly skilled people without tertiary degrees. Yet, as credential inflation theory argues, lower-level degree holders largely lose their rewards due to lower-level tertiary expansion. Nevertheless, higher-level degrees are devalued along with their proliferation only when they are unaccompanied by high cognitive skills. This means, even though their scarcity declines, higher-level degree holders can retain their labour market outcomes insofar as possessing good cognitive skills.

Furthermore, economic rewards for highly skilled personnel without tertiary degrees diminish in tandem with lower-level tertiary expansion, but such penalty for high skills is not confirmed when higher-level teritary expansion occurs. Given these results, the research team coined the term “decredentialization” as a distinct social phenomenon, associated with higher-level tertiary expansion, that devalues credentials per se whilst relatively promoting the role of skills in reward allocation.

Prof Satoshi Araki, Assistant Professor of the Department of Sociology and Social Policy of Lingnan University in Hong Kong, says that these findings are of great importance to both social science research and policy. “Labour market rewards are allocated partly based on the composite of credentials and skills.

The existing literature, however, has paid little attention to (1) the distinction between degrees with and without high skills and (2) the different levels of tertiary education at both the individual and societal levels. Our new theory of “decredentialization” and related evidence paves the way for a better understanding of the economic value of education, credentialism, and much broader social mechanisms of reward allocation,” Prof Araki says.

This study, co-authored by Prof Araki and Prof Takehiko Kariya, Professor at the Department of Sociology and the Nissan Institute of Japanese Studies, Oxford University, was published in the European Sociological Review.