Researchers from the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the University of Florida will use a $7 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy to study how some plants partner with bacteria to create usable nitrogen and to transfer this ability to the bioenergy crop poplar.

Plants that produce their own nitrogen would require less fertilizer, which would save farmers money and reduce the environmental pollution caused by fertilizer runoff into waterways.

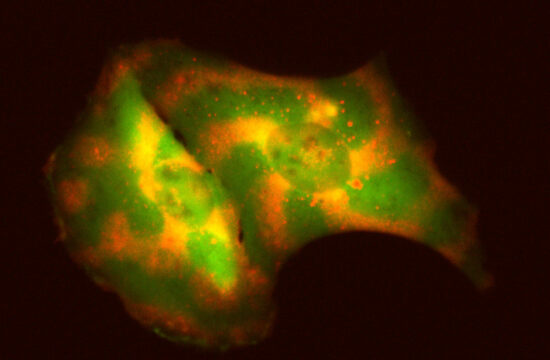

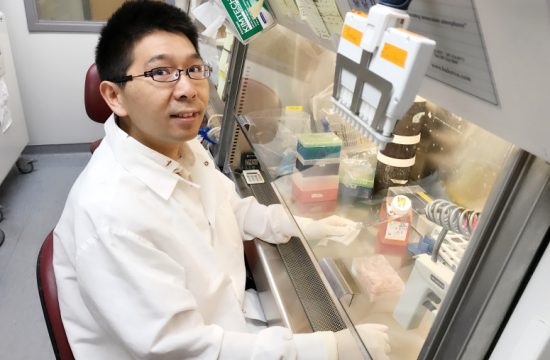

The scientists will study how legumes — alfalfa, beans, and their cousins — evolved the ability to cooperate with bacteria to turn the nitrogen that is so abundant in the air into a form usable by plants. That process is called nitrogen fixation, and it takes place in specialized root organs called nodules that harbor soil bacteria. Recreating this ability in other plants has long been a goal of microbiologists and plant biologists interested in improving agriculture, says Jean-Michel Ané, a professor of bacteriology and agronomy and the lead researcher for the UW–Madison team.

The scientists will use the increasing availability of fully sequenced genomes and datasets on gene expression to investigate the evolutionary history of nitrogen fixation. By comparing closely related plants where one species retains this ability and another has lost it, the researchers can identify the most important genetic elements for nitrogen fixation to take place.

“Most of the time, evolution works by modifying preexisting mechanisms, and we want to find the preexisting mechanisms and key innovations that have been used by evolution to create these new associations between plants and bacteria,” explains Ané. “It is very likely that plants that don’t form nodules, like poplar, have these preexisting mechanisms that we could tweak to create nodules and allow these associations.”

Ané’s group will work with Sushmita Roy, a professor of biostatistics and medical informatics at the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, to lead this evolutionary investigation. The UW–Madison researchers will then partner with colleagues at the University of Florida to begin testing groups of genes that could confer nodulation and bacterial symbiosis — and ultimately nitrogen fixation — on poplar.

Ané says that this project continues a long tradition of studying nitrogen fixation at UW–Madison.

“UW–Madison for decades has been a leader in research on nitrogen fixation, in biochemistry, in agronomy, and in bacteriology. There has been a really long history of research on the enzyme that performs nitrogen fixation,” he says.

While the new grant aims to develop nitrogen fixation in poplar, food crops are also a target. Ané says that the Wisconsin Crop Innovation Center, a plant biotechnology center at UW–Madison, provides the expertise that would be required to translate findings from poplar research to cereals like corn, wheat and rice.

“My hope is that if we find something that works in poplar, then we have the capacity in the Wisconsin Crop Innovation Center, which is fairly unique in the United States, to apply those results to cereals, which I’m really excited about,” says Ané.