Fielding more female candidates helps political parties gain votes.

CAMBRIDGE– Political parties find that their fortunes improve when they put more women on the ballot, according to a study co-authored by an MIT economist.

The study analyzes changes to municipal election laws in Spain, which a decade ago began requiring political parties to have women fill at least 40 percent of the slots on their electoral lists. With other factors being equal, the research found, parties that increased their share of female candidates by 10 percentage points more than their opponents enjoyed a 4.2 percentage-point gain at the ballot box, or an outright switch of about 20 votes per 1,000 cast.

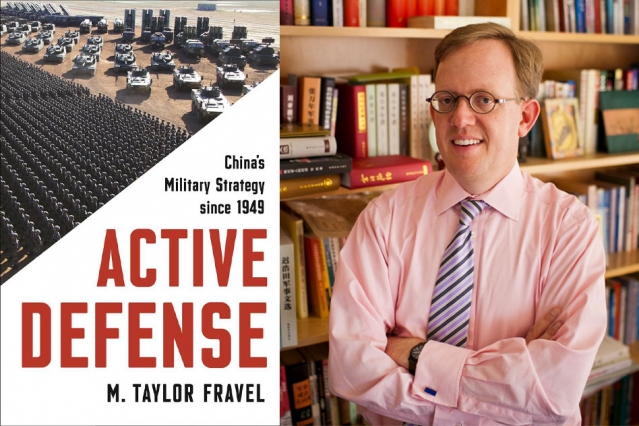

“When you force a party to field more women, they gain votes,” says Albert Saiz, the Daniel Rose Professor of Urban Economics and Real Estate in MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning, and director of MIT’s Center for Real Estate, who is co-author of a forthcoming paper detailing the study.

Saiz believes the study strikes a blow against some common justifications for the dearth of female candidates in many democracies — namely, that voters simply prefer voting for men, or that not enough high-quality female candidates are available to political parties. It is likely that voters will support women, he thinks, and that plenty of good female candidates exist — but women do not appear on ballots as frequently as men because of machinations within party organizations.

“We [believe] that it’s not really about voters,” Saiz says. “It’s about internal dynamics of the parties. There’s some elbowing out going on that leaves women behind.”

Held back?

The forthcoming paper — “Women and Power: Unpopular, Unwilling, or Held Back?” — will appear in the Journal of Political Economy. It is co-authored by Saiz and Pablo Casas-Arce, an assistant professor of economics at Arizona State University.

The study makes adroit use of a “natural experiment,” a real-world circumstance that social scientists can use to examine the causal impact of, say, a policy change within otherwise similar civic conditions. In this case, Spain’s Social Democratic Party enacted an equality law after gaining power in the country’s 2004 parliamentary election. That law, requiring the 40 percent minimum quota of female candidates in local elections, was put into effect for Spain’s 2007 elections.

The law’s rapid enactment challenges the claim that there is a scarcity of qualified female candidates, among other things; if there were such a shortage, it would have been manifest in the elections three years later. As a result of the legislation, the number of female candidates increased by 8.5 percentage points, or 32 percent, compared to 2004.

Spain’s law only applied to municipalities of more than 5,000 people; in some places, parties were already above the 40 percent threshold. So as a further refinement of the analysis, the researchers used towns unaffected by the quota as a control for the study. Saiz and Casas-Arce found that, given these controls, parties still produced the 4.2 percentage-point shift.

“If a party were optimizing, they couldn’t do better if they fielded more females,” Saiz says. “What we find is the opposite.”

No major aversion

While the findings are particular to Spain, the study itself was extensive: All told, the researchers examined elections in 4,852 municipalities. Among their additional findings: Voter turnout did not diminish in response to a greater number of female candidates.

“These results are not consistent with the existence of major voter aversion to female candidates,” the authors write in the paper.

Saiz says he would welcome further research on the subject, including studies of mechanisms that might make it easier for women to become candidates, such as the greater use of party primaries at all levels of politics.

At a minimum, he notes, the study gives parties with a prior lack of female candidates an obvious incentive to remedy that.

“The effect is non-negligible, and it’s positive,” Saiz says.