Scientific expedition will explore Tasman Sea for clues about submerged continent

HOUSTON — Thirty scientists will sail from Australia July 27 on a two-month ocean drilling expedition to the submerged continent of Zealandia in search of clues about its history, which relates to key questions about plate tectonic processes and Earth’s past greenhouse climate.

“We’re really looking at the best place in the world to understand how plate subduction initiates,” said expedition co-chief scientist Gerald Dickens, professor of Earth, environmental and planetary science at Rice University. “This expedition will answer a lot of lingering questions about Zealandia.”

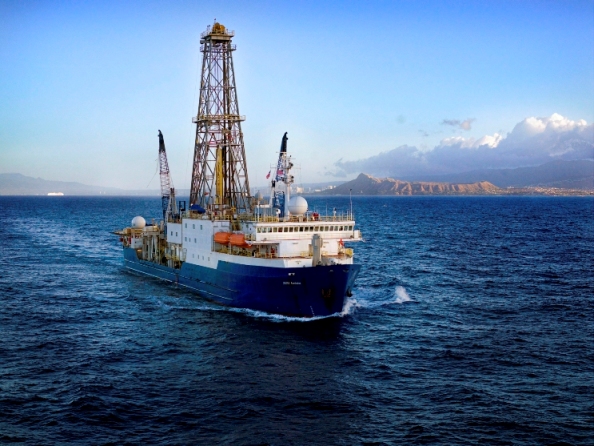

Expedition 371, a cruise sponsored by the National Science Foundation and its international partners in the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP), will sail from Townsville, Australia, aboard JOIDES Resolution, one of the world’s most sophisticated scientific drill ships. Expedition scientists will join more than 20 scientific crew members in drilling at six Tasman Sea sites at water depths ranging from 1,000 to 5,000 meters. At each site, the crew will drill from 300 to 800 meters into the seafloor to collect cores — complete samples of sediments deposited over millions of years. The cores hold fossil evidence the scientists can use to assemble a detailed record of Zealandia’s past.

“Some 50 million years ago a massive shift in plate movement happened in the Pacific Ocean,” said Jamie Allan, program director in the National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences, which supports IODP. “It resulted in the diving of the Pacific Plate under New Zealand, the uplift of New Zealand above the waterline and the development of a new arc of volcanoes. This IODP expedition will look at the timing and causes of these changes, as well as related changes in ocean circulation patterns and ultimately Earth’s climate.”

Zealandia is a mass of continental crust about half the size of Australia that surrounds New Zealand. Increasingly detailed seafloor maps have brought Zealandia into focus in recent decades. Unlike other continents, though, more than 90 percent of Zealandia is submerged.

“If you go way back, about 100 million years ago, Antarctica, Australia and Zealandia were all one continent,” Dickens said. “Around 85 million years ago, Zealandia split off on its own, and for a time, the seafloor between it and Australia was spreading on either side of an ocean ridge that separated the two.”

The relative movements of Zealandia and Australia are due to plate tectonics, the constant movement of interlocking sections of Earth’s surface. There are some 25 tectonic plates that fit like puzzle pieces to form Earth’s crust. Plates are in constant motion. They can crash together to form mountain ranges and slide past one another in earthquake zones. Oceanic plates form on either side of ocean ridges and also can slide beneath lighter, more buoyant continental plates in a process known as subduction.

Expedition 371 will examine a shift that occurred about 50 million years ago in the direction of movement of the enormous Pacific Plate northeast of Zealandia. In its scientific prospectus, the expedition refers to this shift as “the most profound subduction initiation event and global plate-motion change” in the past 80 million years. Prior to the shift, Australia and New Zealand were spreading apart, and after the shift, the area that separated them was under compression for millions of years. Then, in the final stage of the tectonic shift, the Pacific Plate dove beneath Zealandia, forming a new subduction zone. This relieved the compressive forces across the region.

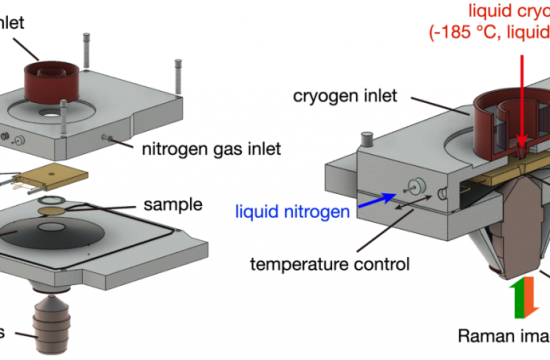

“What we want to understand is why and when the various stages from extension to relaxation occurred,” Dickens said. “The cores will help tell us that. They’ll be analyzed for sediment composition, microfossil components, mineral and water chemistry and physical properties.”

He said the research also could answer many questions about the way Earth’s climate has evolved in the last 60 million years. For example, Zealandia is left out of many climate models, and Dickens said this could be one reason that this region has been among the most difficult parts of Earth to accurately model in greenhouse climates around 50 million years ago.

“When the community does climate modeling for the Eocene (Epoch), this is the area that causes consternation, and we’re not sure why,” he said. “It may be because we had continents that were much shallower than we had thought. Or we could have the continents right but at the wrong latitude. Either way, the cores will help us figure that out.”

IODP is an international research collaboration that coordinates seagoing expeditions to study the history of Earth recorded in sediments and rocks beneath the ocean floor. Scientists apply to participate in IODP expeditions, and participation is open to all scientists from IODP’s member countries. Opportunities exist for researchers, including graduate students, in all shipboard specialties, which include but are not limited to sedimentology, micropaleontology, paleomagnetism, inorganic/organic geochemistry, petrology, petrophysics, microbiology and borehole geophysics.